3. Machine Learning Models

Machine learning (ML) is a subfield of artificial intelligence (AI) focused on developing algorithms and statistical models that enable computers to learn from and make decisions based on data. Unlike traditional programming, where explicit instructions are given, machine learning systems identify patterns and insights from large datasets, improving their performance over time through experience.

ML encompasses various techniques, including supervised learning, where models are trained on labeled data to predict outcomes; unsupervised learning, which involves discovering hidden patterns or groupings within unlabeled data; and reinforcement learning, where models learn optimal actions through trial and error in dynamic environments. These methods are applied across diverse domains, from natural language processing and computer vision to recommendation systems and autonomous vehicles, revolutionizing how technology interacts with the world.

3.1 Decision Tree and Random Forest

3.1.1 Decision Trees

Decision Trees are intuitive and powerful models used in machine learning to make predictions and decisions. Think of it like playing a game of 20 questions, where each question helps you narrow down the possibilities. Decision trees function similarly; they break down a complex decision into a series of simpler questions based on the data.

Each question, referred to as a “decision,” relies on a specific characteristic or feature of the data. For instance, if you’re trying to determine whether a fruit is an apple or an orange, the initial question might be, “Is the fruit’s color red or orange?” Depending on the answer, you might follow up with another question—such as, “Is the fruit’s size small or large?” This questioning process continues until you narrow it down to a final answer (e.g., the fruit is either an apple or an orange).

In a decision tree, these questions are represented as nodes, and the possible answers lead to different branches. The final outcomes are represented at the end of each branch, known as leaf nodes. One of the key advantages of decision trees is their clarity and ease of understanding—much like a flowchart. However, they can also be prone to overfitting, especially when dealing with complex datasets that have many features. Overfitting occurs when a model performs exceptionally well on training data but fails to generalize to new or unseen data.

In summary, decision trees offer an intuitive approach to making predictions and decisions, but caution is required to prevent them from becoming overly complicated and tailored too closely to the training data.

3.1.2 Random Forest

Random Forests address the limitations of decision trees by utilizing an ensemble of multiple trees instead of relying on a single one. Imagine you’re gathering opinions about a game outcome from a group of people; rather than trusting just one person’s guess, you ask everyone and then take the most common answer. This is the essence of how a Random Forest operates.

In a Random Forest, numerous decision trees are constructed, each making its own predictions. However, a key difference is that each tree is built using a different subset of the data and considers different features of the data. This technique, known as bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating), allows each tree to provide a unique perspective, which collectively leads to a more reliable prediction.

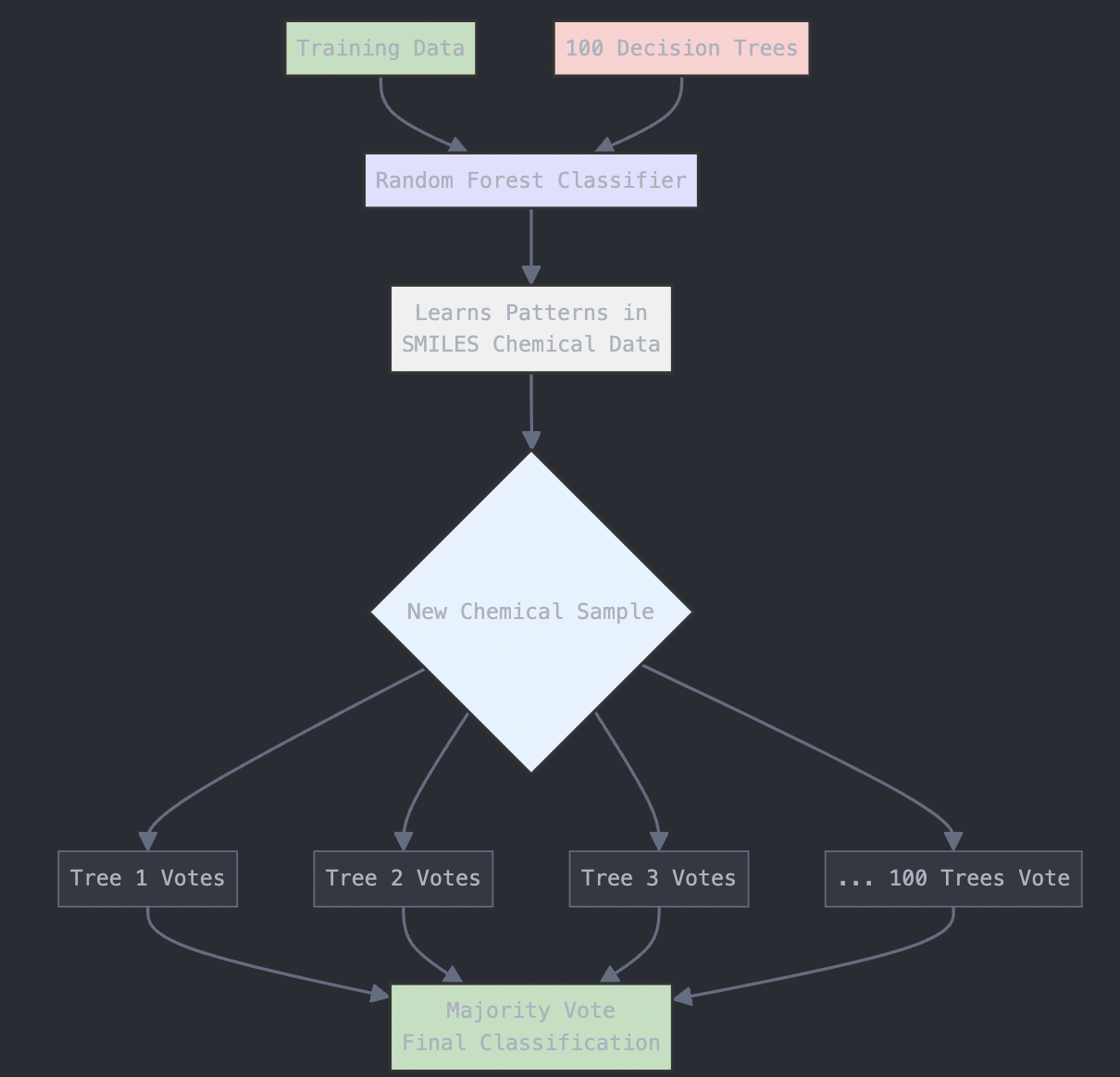

When making a final prediction, the Random Forest aggregates the predictions from all the trees. For classification tasks, it employs majority voting to determine the final class label, while for regression tasks, it averages the results.

Random Forests typically outperform individual decision trees because they are less likely to overfit the data. By combining multiple trees, they achieve a balance between model complexity and predictive performance on unseen data.

Real-Life Analogy

Consider Andrew, who wants to decide on a destination for his year-long vacation. He starts by asking his close friends for suggestions. The first friend asks Andrew about his past travel preferences, using his answers to recommend a destination. This is akin to a decision tree approach—one friend following a rule-based decision process.

Next, Andrew consults more friends, each of whom poses different questions to gather recommendations. Finally, Andrew chooses the places suggested most frequently by his friends, mirroring the Random Forest algorithm’s method of aggregating multiple decision trees’ outputs.

3.1.3 Implementing Random Forest on the BBBP Dataset

This guide demonstrates how to implement a Random Forest algorithm in Python using the BBBP (Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability) dataset. The BBBP dataset is used in cheminformatics to predict whether a compound can cross the blood-brain barrier based on its chemical structure.

The dataset contains SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings representing chemical compounds, and a target column that indicates whether the compound is permeable to the blood-brain barrier or not.

The goal is to predict whether a given chemical compound will cross the blood-brain barrier, based on its molecular structure. This guide walks you through downloading the dataset, processing it, and training a Random Forest model.

Step 1: Install RDKit (Required for SMILES to Fingerprint Conversion)

We need to use the RDKit library, which is essential for converting SMILES strings into molecular fingerprints, a numerical representation of the molecule.

# Install the RDKit package via conda-forge

!pip install -q condacolab

import condacolab

condacolab.install()

# Now install RDKit

!mamba install -c conda-forge rdkit -y

# Import RDKit and check if it's installed successfully

from rdkit import Chem

print("RDKit is successfully installed!")

Step 2: Download the BBBP Dataset from Kaggle

The BBBP dataset is hosted on Kaggle, a popular platform for datasets and machine learning competitions. To access the dataset, you need a Kaggle account and an API key for authentication. Here’s how you can set it up:

Step 2.1: Create a Kaggle Account

- Visit Kaggle and create an account if you don’t already have one.

- Once you’re logged in, go to your profile by clicking on your profile picture in the top right corner, and select My Account.

Step 2.2: Set Up the Kaggle API Key

- Scroll down to the section labeled API on your account page.

- Click on the button “Create New API Token”. This will download a file named kaggle.json to your computer.

- Keep this file safe! It contains your API key, which you’ll use to authenticate when downloading datasets.

Step 2.3: Upload the Kaggle API Key

Once you have the kaggle.json file, you need to upload it to your Python environment:

- If you’re using a notebook environment like Google Colab, use the code below to upload the file:

# Upload the kaggle.json file from google.colab import

files uploaded = files.upload()

# Move the file to the right directory for authentication

!mkdir -p ~/.kaggle !mv kaggle.json ~/.kaggle/ !chmod 600 ~/.kaggle/kaggle.json

- If you’re using a local Jupyter Notebook:

Place the kaggle.json file in a folder named .kaggle within your home directory:

- On Windows: Place it in C:\Users<YourUsername>.kaggle.

- On Mac/Linux: Place it in ~/.kaggle.

Step 2.4: Install the Required Libraries

To interact with Kaggle and download the dataset, you need the Kaggle API client. Install it with the following command:

!pip install kaggle

Step 2.5: Download the BBBP Dataset

Now that the API key is set up, you can download the dataset using the Kaggle API:

# Download the BBBP dataset using the Kaggle API

!kaggle datasets download -d priyanagda/bbbp-smiles

# Unzip the downloaded file

!unzip bbbp-smiles.zip -d bbbp_dataset

This code will:

- Download the dataset into your environment.

- Extract the dataset files into a folder named bbbp_dataset.

Step 2.6: Verify the Download

After downloading, check the dataset files to confirm that everything is in place:

# List the files in the dataset folder

import os

dataset_path = "bbbp_dataset"

files = os.listdir(dataset_path)

print("Files in the dataset:", files)

By following these steps, you will have successfully downloaded and extracted the BBBP dataset, ready for further analysis and processing.

Step 3: Load the BBBP Dataset

After downloading the dataset, we’ll load the BBBP dataset into a pandas DataFrame. The dataset contains the SMILES strings and the target variable (p_np), which indicates whether the compound can cross the blood-brain barrier (binary classification: 1 for permeable, 0 for non-permeable).

import pandas as pd

# Load the BBBP dataset (adjust the filename if it's different)

data = pd.read_csv("bbbp.csv") # Assuming the dataset is named bbbp.csv

print("Dataset Head:", data.head())

Step 4: Convert SMILES to Molecular Fingerprints

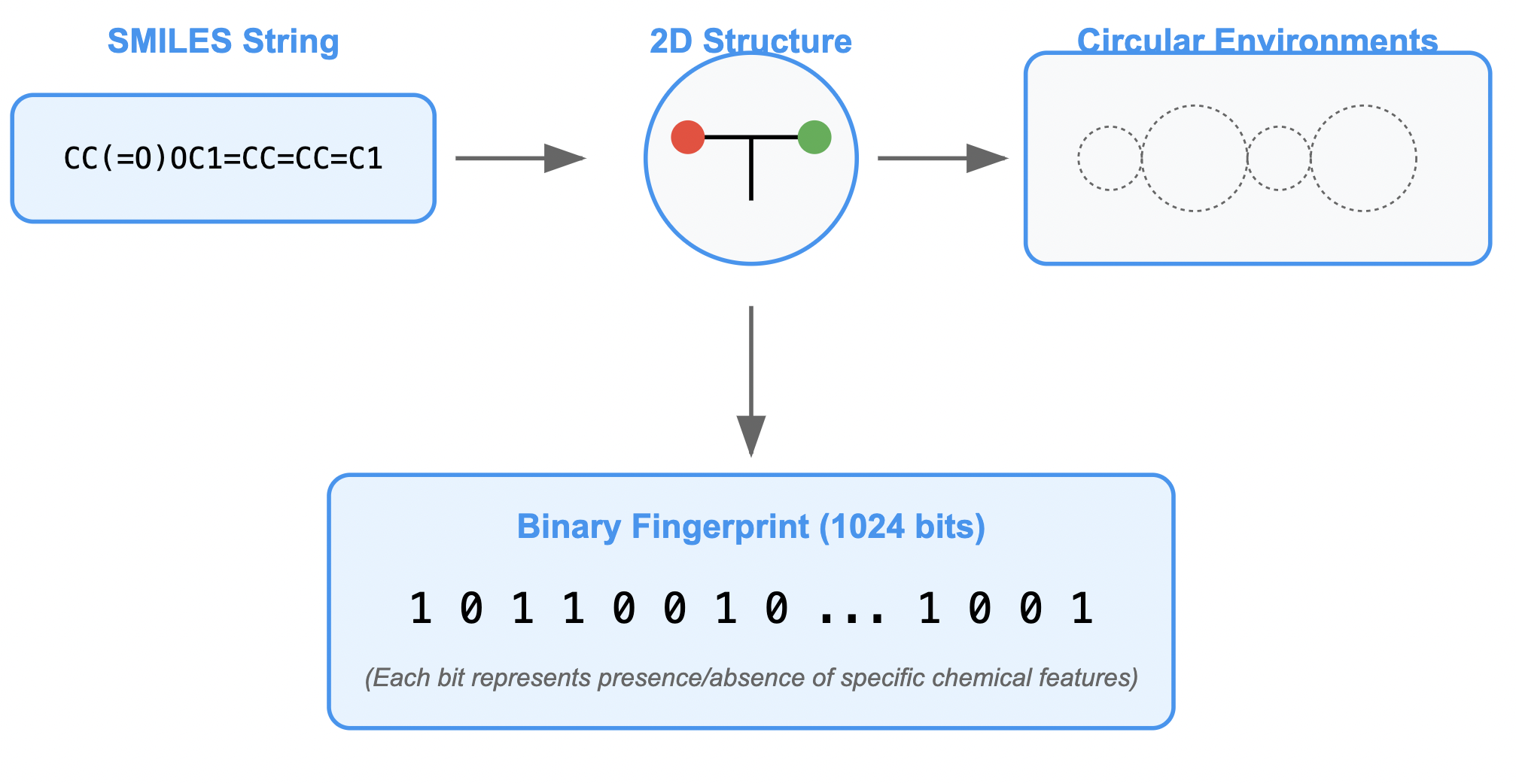

To use the SMILES strings for modeling, we need to convert them into molecular fingerprints. This process turns the chemical structures into a numerical format that can be fed into machine learning models. We’ll use RDKit to generate these fingerprints using the Morgan Fingerprint method.

from rdkit import Chem

from rdkit.Chem import AllChem

import numpy as np

# Function to convert SMILES to molecular fingerprints

def featurize_molecule(smiles):

mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles(smiles)

if mol:

return AllChem.GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVect(mol, 2, nBits=1024)

else:

return None

# Apply featurization to the dataset

features = [featurize_molecule(smi) for smi in data['smiles']] # Replace 'smiles' with the actual column name if different

features = [list(fp) if fp is not None else np.zeros(1024) for fp in features] # Handle missing data by filling with zeros

X = np.array(features)

y = data['p_np'] # Target column (1 for permeable, 0 for non-permeable)

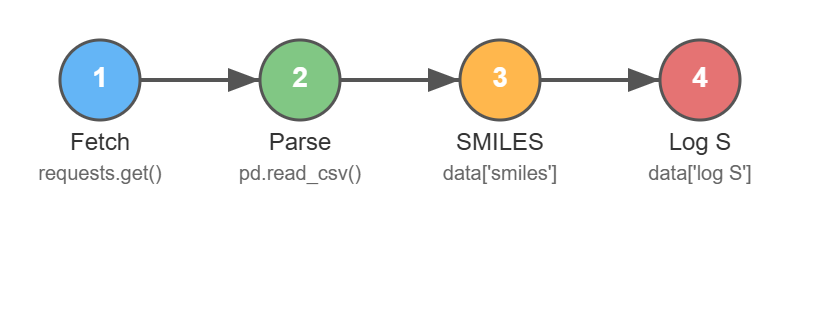

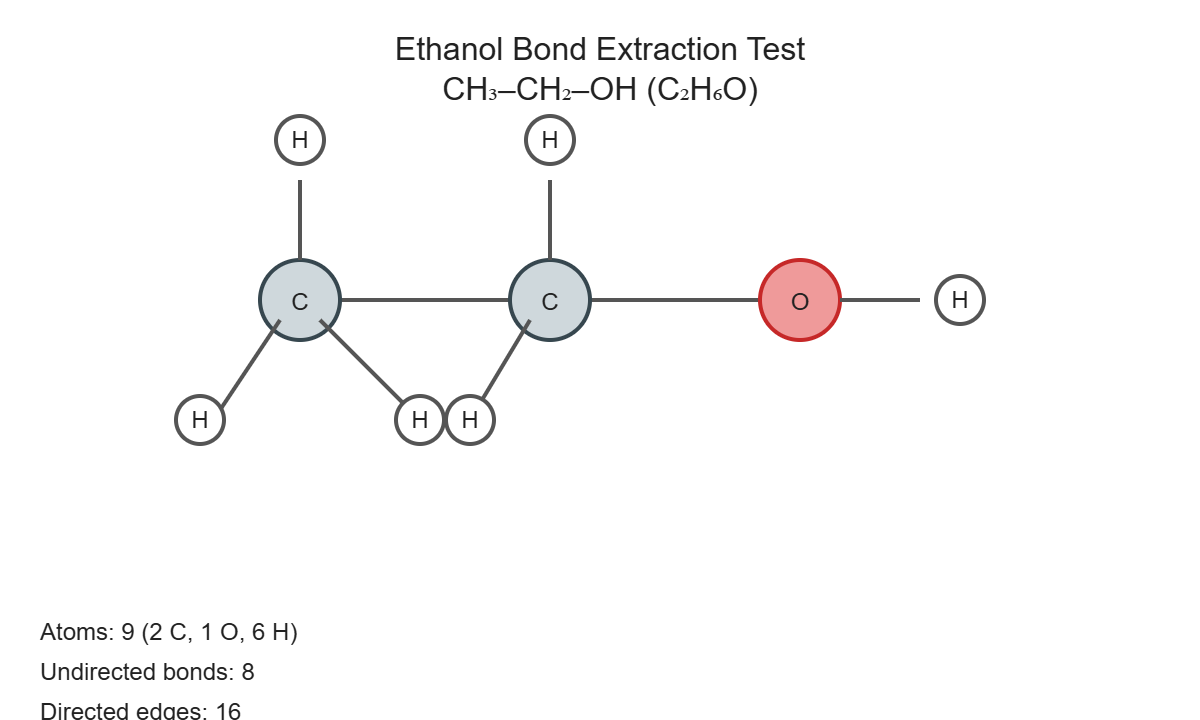

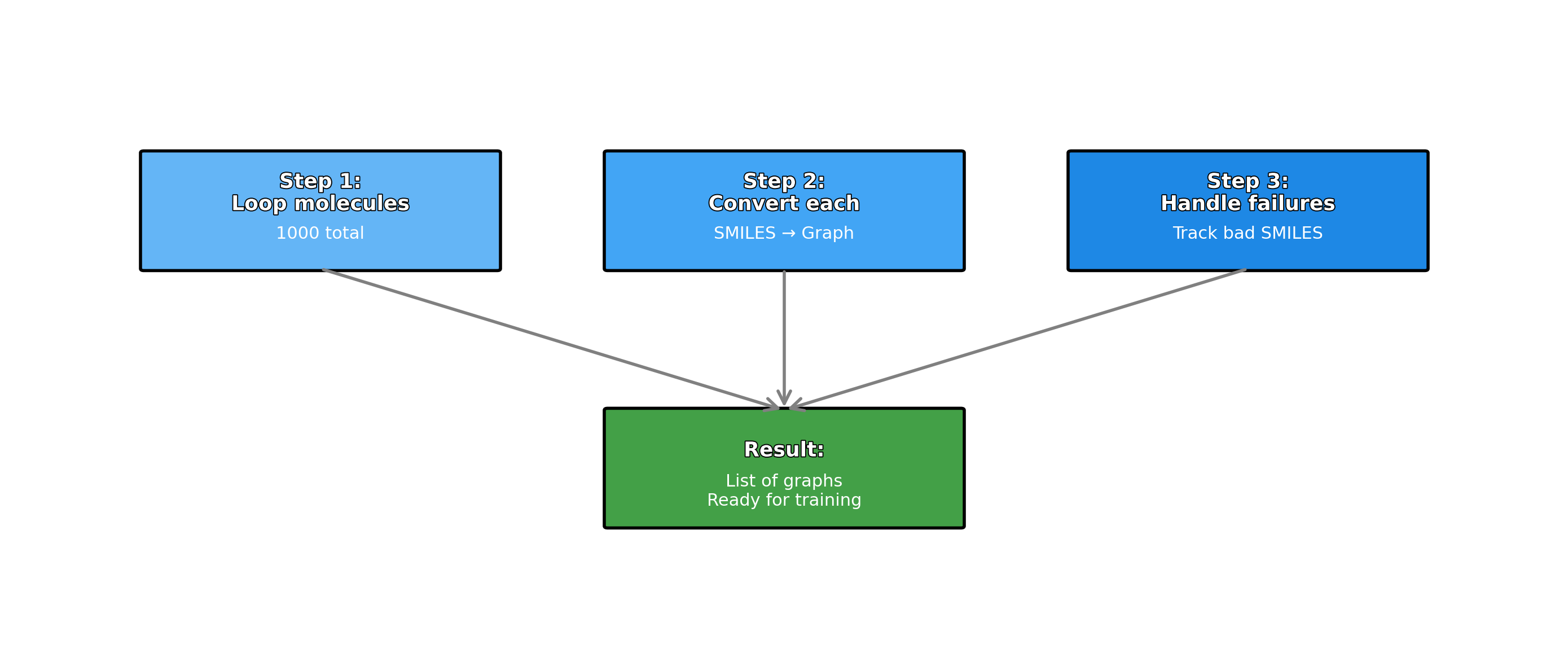

The diagram below provides a visual representation of what this code does:

Figure: SMILES to Molecular Fingerprints Conversion Process

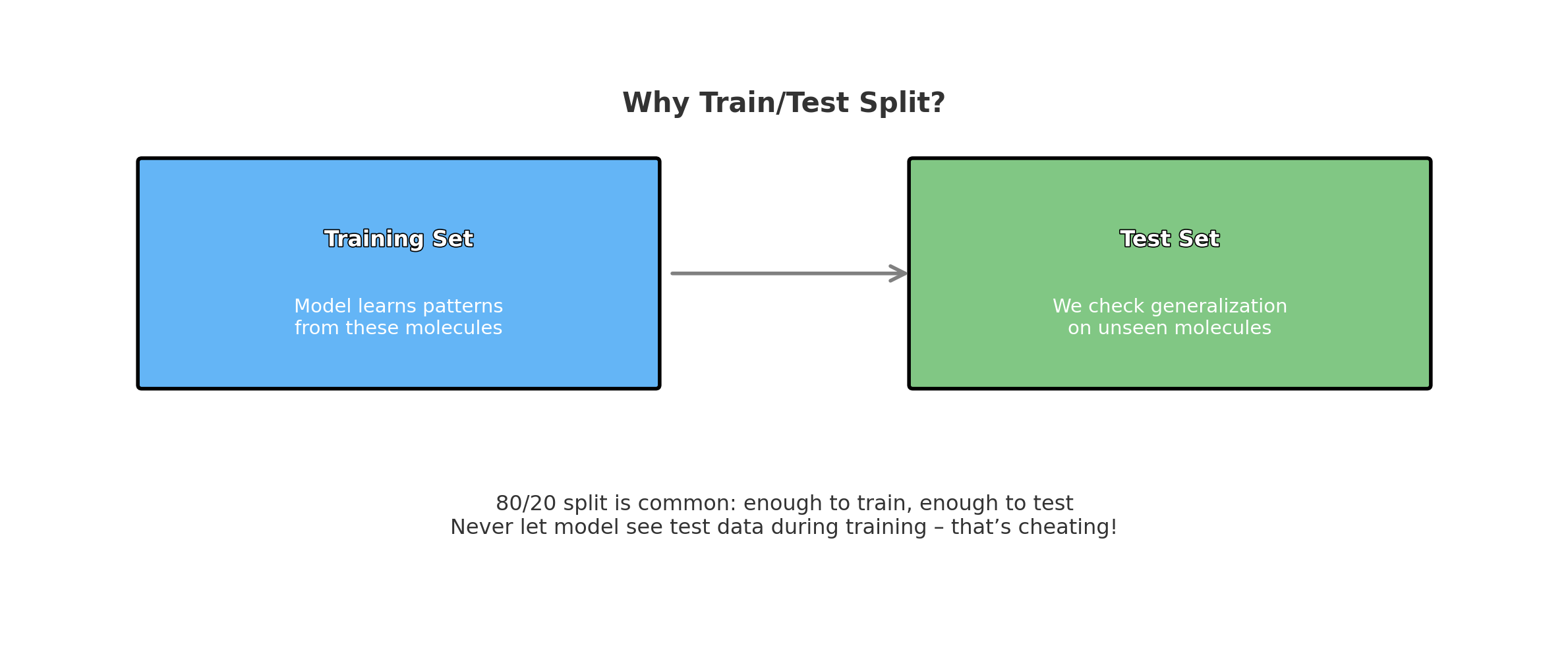

Step 5: Split Data into Training and Testing Sets

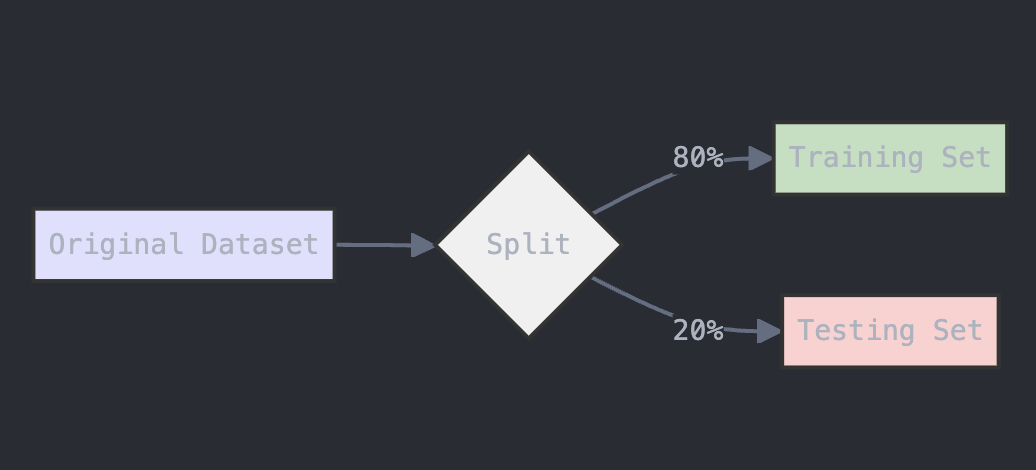

To evaluate the model, we need to split the data into training and testing sets. The train_test_split function from scikit-learn will handle this. We’ll use 80% of the data for training and 20% for testing.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Split data into train and test sets (80% training, 20% testing)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

The diagram below provides a visual representation of what this code does:

Figure: Data Splitting Process for Training and Testing

Step 6: Train the Random Forest Model

We’ll use the RandomForestClassifier from scikit-learn to build the model. A Random Forest is an ensemble method that uses multiple decision trees to make predictions. The more trees (n_estimators) we use, the more robust the model will be, but the longer the model will take to run. For the most part, n_estimators is set to 100 in most versions of scikit-learn. However, for more complex datasets, higher values like 500 or 1000 may improve performance.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

# Train a Random Forest classifier

rf_model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100, random_state=42)

rf_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

The diagram below provides a visual explanation of what is going on here:

Figure: Random Forest Algorithm Structure

Step 7: Evaluate the Model

After training the model, we’ll use the test data to evaluate its performance. We will print the accuracy and the classification report to assess the model’s precision, recall, and F1 score.

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, classification_report

# Predictions on the test set

y_pred = rf_model.predict(X_test)

# Evaluate accuracy and performance

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

print("Accuracy:", accuracy)

print("Classification Report:", classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

Model Performance and Parameters

- Accuracy: The proportion of correctly predicted instances out of all instances.

- Classification Report: Provides additional metrics like precision, recall, and F1 score.

In this case, we achieved an accuracy score of ~87%.

Key Hyperparameters:

- n_estimators: The number of trees in the Random Forest. More trees generally lead to better performance but also require more computational resources.

- test_size: The proportion of data used for testing. A larger test size gives a more reliable evaluation but reduces the amount of data used for training.

- random_state: Ensures reproducibility by initializing the random number generator to a fixed seed.

Conclusion

This guide demonstrated how to implement a Random Forest model to predict the Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability (BBBP) using the BBBP dataset. By converting SMILES strings to molecular fingerprints and using a Random Forest classifier, we were able to achieve an accuracy score of around 87%.

Adjusting parameters like the number of trees (n_estimators) or the split ratio (test_size) can help improve the model’s performance. Feel free to experiment with these parameters and explore other machine learning models for this task!

3.1.4 Approaching Random Forest Problems

When tackling a classification or regression problem using the Random Forest algorithm, a systematic approach can enhance your chances of success. Here’s a step-by-step guide to effectively solve any Random Forest problem:

-

Understand the Problem Domain: Begin by thoroughly understanding the problem you are addressing. Identify the nature of the data and the specific goal—whether it’s classification (e.g., predicting categories) or regression (e.g., predicting continuous values). Familiarize yourself with the dataset, including the features (independent variables) and the target variable (dependent variable).

-

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Gather the relevant dataset and perform necessary preprocessing steps. This may include handling missing values, encoding categorical variables, normalizing or standardizing numerical features, and removing any outliers. Proper data cleaning ensures that the model learns from quality data.

-

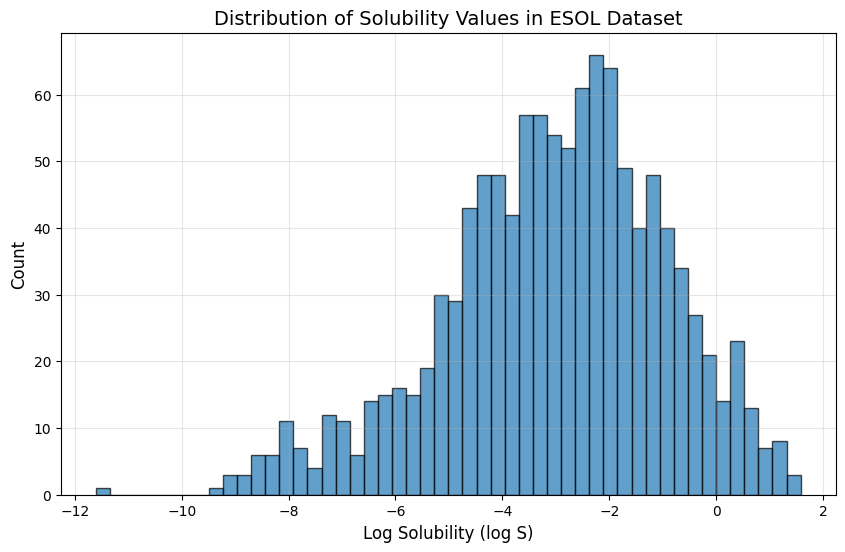

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA): Conduct an exploratory data analysis to understand the underlying patterns, distributions, and relationships within the data. Visualizations, such as scatter plots, histograms, and correlation matrices, can provide insights that inform feature selection and model tuning.

-

Feature Selection and Engineering: Identify the most relevant features for the model. This can be achieved through domain knowledge, statistical tests, or feature importance metrics from preliminary models. Consider creating new features through feature engineering to enhance model performance.

-

Model Training and Parameter Tuning: Split the dataset into training and testing sets, typically using an 80-20 or 70-30 ratio. Train the Random Forest model using the training data, adjusting parameters such as the number of trees (

n_estimators), the maximum depth of the trees (max_depth), and the minimum number of samples required to split an internal node (min_samples_split). Utilize techniques like grid search or random search to find the optimal hyperparameters. -

Model Evaluation: Once trained, evaluate the model’s performance on the test set using appropriate metrics. For classification problems, metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and ROC-AUC are valuable. For regression tasks, consider metrics like mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), and R-squared.

-

Interpretation and Insights: Analyze the model’s predictions and feature importance to derive actionable insights. Understanding which features contribute most to the model can guide decision-making and further improvements in the model or data collection.

-

Iterate and Improve: Based on the evaluation results, revisit the previous steps to refine your model. This may involve further feature engineering, collecting more data, or experimenting with different algorithms alongside Random Forest to compare performance.

-

Deployment: Once satisfied with the model’s performance, prepare it for deployment. Ensure the model can process incoming data and make predictions in a real-world setting, and consider implementing monitoring tools to track its performance over time.

By following this structured approach, practitioners can effectively leverage the Random Forest algorithm to solve a wide variety of problems, ensuring thorough analysis, accurate predictions, and actionable insights.

3.1.5 Strengths and Weaknesses of Random Forest

Strengths:

-

Robustness: Random Forests are less prone to overfitting compared to individual decision trees, making them more reliable for new data.

-

Versatility: They can handle both classification and regression tasks effectively.

-

Feature Importance: Random Forests provide insights into the significance of each feature in making predictions.

Weaknesses:

-

Complexity: The model can become complex, making it less interpretable than single decision trees.

-

Resource Intensive: Training a large number of trees can require significant computational resources and time.

-

Slower Predictions: While individual trees are quick to predict, aggregating predictions from multiple trees can slow down the prediction process.

Section 3.1 – Quiz Questions

1) Factual Questions

Question 1

What is the primary reason a Decision Tree might perform very well on training data but poorly on new, unseen data?

A. Underfitting

B. Data leakage

C. Overfitting

D. Regularization

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Decision Trees can easily overfit the training data by creating very complex trees that capture noise instead of general patterns. This hurts their performance on unseen data.Question 2

In a Decision Tree, what do the internal nodes represent?

A. Possible outcomes

B. Splitting based on a feature

C. Aggregation of multiple trees

D. Random subsets of data

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: B▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Internal nodes represent decision points where the dataset is split based on the value of a specific feature (e.g., "Is the fruit color red or orange?").Question 3

Which of the following best explains the Random Forest algorithm?

A. A single complex decision tree trained on all the data

B. Many decision trees trained on identical data to improve depth

C. Many decision trees trained on random subsets of the data and features

D. A clustering algorithm that separates data into groups

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Random Forests use bagging to train multiple decision trees on different random subsets of the data and different random subsets of features, making the ensemble more robust.Question 4

When training a Random Forest for a classification task, how is the final prediction made?

A. By taking the median of the outputs

B. By taking the average of probability outputs

C. By majority vote among trees’ predictions

D. By selecting the tree with the best accuracy

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: For classification problems, the Random Forest algorithm uses majority voting — the class most predicted by the individual trees becomes the final prediction.2) Conceptual Questions

Question 5

You are given a dataset containing information about chemical compounds, with many categorical features (such as “molecular class” or “bond type”).

Would using a Random Forest model be appropriate for this dataset?

A. No, Random Forests cannot handle categorical data.

B. Yes, Random Forests can naturally handle datasets with categorical variables after encoding.

C. No, Random Forests only work on images.

D. Yes, but only if the dataset has no missing values.

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: B▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Random Forests can handle categorical data after simple preprocessing, such as label encoding or one-hot encoding. They are robust to different feature types, including numerical and categorical.Question 6

Suppose you have your molecule fingerprints stored in variables X and your labels (0 or 1 for BBBP) stored in y.

Which of the following correctly splits the data into 80% training and 20% testing sets?

A.

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, train_size=0.2, random_state=42)

B.

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

C.

X_train, X_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.8, random_state=42)

D.

X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: B▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: In Random Forest modeling, we use train_test_split from sklearn.model_selection. test_size=0.2 reserves 20% of the data for testing, leaving 80% for training. The function returns train features, test features, train labels, and test labels — in that exact order: X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42) A, C, and D are wrong because... (A) reverses train and test sizing. (C) mistakenly sets test_size=0.8 (which would leave only 20% for training — wrong). (D) messes up the return order (train features and labels must come first).▶ Show Solution Code

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

3.2 Neural Network

A neural network is a computational model inspired by the neural structure of the human brain, designed to recognize patterns and learn from data. It consists of layers of interconnected nodes, or neurons, which process input data through weighted connections.

Structure: Neural networks typically include an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each neuron in a layer is connected to neurons in the adjacent layers. The input layer receives data, the hidden layers transform this data through various operations, and the output layer produces the final prediction or classification.

Functioning: Data is fed into the network, where each neuron applies an activation function to its weighted sum of inputs. These activation functions introduce non-linearity, allowing the network to learn complex patterns. The output of the neurons is then passed to the next layer until the final prediction is made.

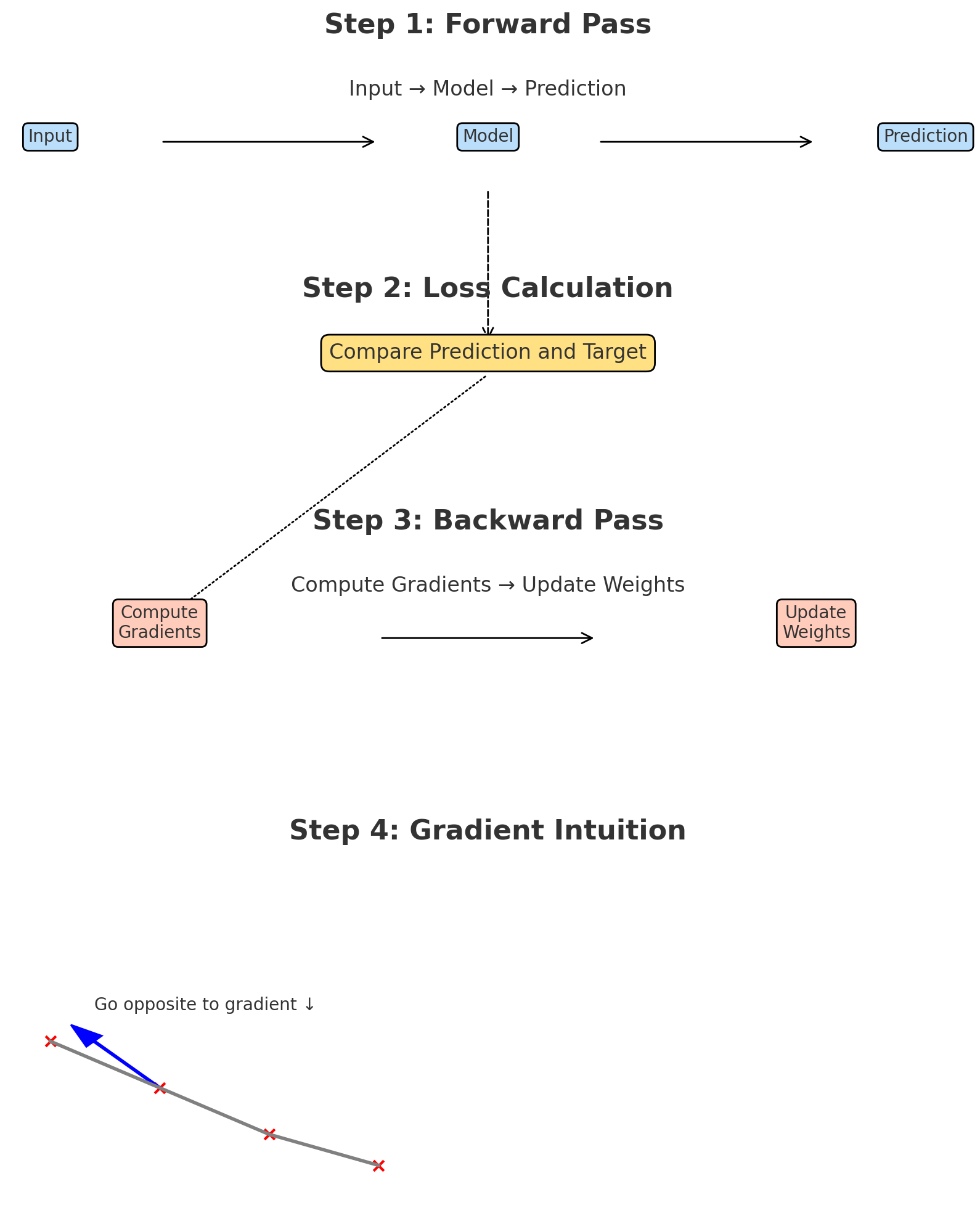

Learning Process: Neural networks learn through a process called training. During training, the network adjusts the weights of connections based on the error between its predictions and the actual values. This is achieved using algorithms like backpropagation and optimization techniques such as gradient descent, which iteratively updates the weights to minimize the prediction error.

3.2.1 Biological and Conceptual Foundations of Neural Networks

Neural networks are a class of machine learning models designed to learn patterns from data in order to make predictions or classifications. Their structure and behavior are loosely inspired by how the human brain processes information: through a large network of connected units that transmit signals to each other. Although artificial neural networks are mathematical rather than biological, this analogy provides a helpful starting point for understanding how they function.

The Neural Analogy

In a biological system, neurons receive input signals from other neurons, process those signals, and send output to downstream neurons. Similarly, an artificial neural network is composed of units called “neurons” or “nodes” that pass numerical values from one layer to the next. Each of these units receives inputs, processes them using a simple rule, and forwards the result.

This structure allows the network to build up an understanding of the input data through multiple layers of transformations. As information flows forward through the network—layer by layer—it becomes increasingly abstract. Early layers may focus on basic patterns in the input, while deeper layers detect more complex or chemically meaningful relationships.

Layers of a Neural Network

Neural networks are organized into three main types of layers:

- Input Layer: This is where the network receives the data. In chemistry applications, this might include molecular fingerprints, structural descriptors, or other numerical representations of a molecule.

- Hidden Layers: These are the internal layers where computations happen. The network adjusts its internal parameters to best relate the input to the desired output.

- Output Layer: This layer produces the final prediction. For example, it might output a predicted solubility value, a toxicity label, or the probability that a molecule is biologically active.

The depth (number of layers) and width (number of neurons in each layer) of a network affect its capacity to learn complex relationships.

Why Chemists Use Neural Networks

Many molecular properties—such as solubility, lipophilicity, toxicity, and biological activity—are influenced by intricate, nonlinear combinations of atomic features and substructures. These relationships are often difficult to express with a simple equation or rule.

Neural networks are especially useful in chemistry because:

- They can learn from large, complex datasets without needing detailed prior knowledge about how different features should be weighted.

- They can model nonlinear relationships, such as interactions between molecular substructures, electronic effects, and steric hindrance.

- They are flexible and can be applied to a wide range of tasks, from predicting reaction outcomes to screening drug candidates.

How Learning Happens

Unlike hardcoded rules, neural networks improve through a process of learning:

- Prediction: The network uses its current understanding to make a guess about the output (e.g., predicting a molecule’s solubility).

- Feedback: It compares its prediction to the known, correct value.

- Adjustment: It updates its internal parameters to make better predictions next time.

This process repeats over many examples, gradually improving the model’s accuracy. Over time, the network can generalize—making reliable predictions on molecules it has never seen before.

3.2.2 The Structure of a Neural Network

Completed and Compiled Code: Click Here

The structure of a neural network refers to how its components are organized and how information flows from the input to the output. Understanding this structure is essential for applying neural networks to chemical problems, where numerical data about molecules must be transformed into meaningful predictions—such as solubility, reactivity, toxicity, or classification into chemical groups.

Basic Building Blocks

A typical neural network consists of three types of layers:

- Input Layer

This is the first layer and represents the data you give the model. In chemistry, this might include:

- Molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan or ECFP4)

- Descriptor vectors (e.g., molecular weight, number of rotatable bonds)

- Graph embeddings (in more advanced architectures)

Each input feature corresponds to one “neuron” in this layer. The network doesn’t modify the data here; it simply passes it forward.

- Hidden Layers

These are the core of the network. They are composed of interconnected neurons that process the input data through a series of transformations. Each neuron:

- Multiplies each input by a weight (a learned importance factor)

- Adds the results together, along with a bias term

- Passes the result through an activation function to determine the output

Multiple hidden layers can extract increasingly abstract features. For example:

- First hidden layer: detects basic structural motifs (e.g., aromatic rings)

- Later hidden layers: model higher-order relationships (e.g., presence of specific pharmacophores)

The depth of a network (number of hidden layers) increases its capacity to model complex patterns, but also makes it more challenging to train.

- Output Layer

This layer generates the final prediction. The number of output neurons depends on the type of task:

- One neuron for regression (e.g., predicting solubility)

- One neuron with a sigmoid function for binary classification (e.g., active vs. inactive)

- Multiple neurons with softmax for multi-class classification (e.g., toxicity categories)

Activation Functions

The activation function introduces non-linearity to the model. Without it, the network would behave like a linear regression model, unable to capture complex relationships. Common activation functions include:

- ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): Returns 0 for negative inputs and the input itself for positive values. Efficient and widely used.

- Sigmoid: Squeezes inputs into the range (0,1), useful for probabilities.

- Tanh: Similar to sigmoid but outputs values between -1 and 1, often used in earlier layers.

These functions allow neural networks to model subtle chemical relationships, such as how a substructure might enhance activity in one molecular context but reduce it in another.

Forward Pass: How Data Flows Through the Network

The process of making a prediction is known as the forward pass. Here’s what happens step-by-step:

- Each input feature (e.g., molecular weight = 300) is multiplied by a corresponding weight.

- The weighted inputs are summed and combined with a bias.

- The result is passed through the activation function.

- The output becomes the input to the next layer.

This process repeats until the final output is produced.

Building a Simple Neural Network for Molecular Property Prediction

Let’s build a minimal neural network that takes molecular descriptors as input and predicts a continuous chemical property, such as aqueous solubility. We’ll use TensorFlow and Keras.

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow.keras import layers, models

import numpy as np

# Example molecular descriptors for 5 hypothetical molecules:

# Features: [Molecular Weight, LogP, Number of Rotatable Bonds]

X = np.array([

[180.1, 1.2, 3],

[310.5, 3.1, 5],

[150.3, 0.5, 2],

[420.8, 4.2, 8],

[275.0, 2.0, 4]

])

# Target values: Normalized aqueous solubility

y = np.array([0.82, 0.35, 0.90, 0.20, 0.55])

# Define a simple feedforward neural network

model = models.Sequential([

layers.Input(shape=(3,)), # 3 input features per molecule

layers.Dense(8, activation='relu'), # First hidden layer

layers.Dense(4, activation='relu'), # Second hidden layer

layers.Dense(1) # Output layer (regression)

])

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='mse') # Mean Squared Error for regression

# Train the model

model.fit(X, y, epochs=100, verbose=0)

# Predict on new data

new_molecule = np.array([[300.0, 2.5, 6]])

predicted_solubility = model.predict(new_molecule)

print("Predicted Solubility:", predicted_solubility[0][0])

Results

Predicted Solubility: 13.366545

What This Code Does:

- Inputs are numerical molecular descriptors (easy for chemists to relate to).

- The model learns a pattern from these descriptors to predict solubility.

- Layers are built exactly as explained: input → hidden (ReLU) → output.

- The output is a single continuous number, suitable for regression tasks.

Practice Problem 3: Neural Network Warm-Up

Using the logic from the code above:

- Replace the input features with the following descriptors:

- [350.2, 3.3, 5], [275.4, 1.8, 4], [125.7, 0.2, 1]

- Create a new NumPy array called X_new with those values.

- Use the trained model to predict the solubility of each new molecule.

- Print the outputs with a message like: “Predicted solubility for molecule 1: 0.67”

# Step 1: Create new molecular descriptors for prediction

X_new = np.array([

[350.2, 3.3, 5],

[275.4, 1.8, 4],

[125.7, 0.2, 1]

])

# Step 2: Use the trained model to predict solubility

predictions = model.predict(X_new)

# Step 3: Print each result with a message

for i, prediction in enumerate(predictions):

print(f"Predicted solubility for molecule {i + 1}: {prediction[0]:.2f}")

Discussion: What Did We Just Do?

In this practice problem, we used a trained neural network to predict the solubility of three new chemical compounds based on simple molecular descriptors. Each molecule was described using three features:

- Molecular weight

- LogP (a measure of lipophilicity)

- Number of rotatable bonds

The model, having already learned patterns from prior data during training, applied its internal weights and biases to compute a prediction for each molecule.

Predicted solubility for molecule 1: 0.38

Predicted solubility for molecule 2: 0.55

Predicted solubility for molecule 3: 0.91

These values reflect the model’s confidence in how soluble each molecule is, with higher numbers generally indicating better solubility. While we don’t yet know how the model arrived at these exact numbers (that comes in the next section), this exercise demonstrates a key advantage of neural networks:

- Once trained, they can generalize to unseen data—making predictions for new molecules quickly and efficiently.

3.2.3 How Neural Networks Learn: Backpropagation and Loss Functions

Completed and Compiled Code: Click Here

In the previous section, we saw how a neural network can take molecular descriptors as input and generate predictions, such as aqueous solubility. However, this raises an important question: how does the network learn to make accurate predictions in the first place? The answer lies in two fundamental concepts: the loss function and backpropagation.

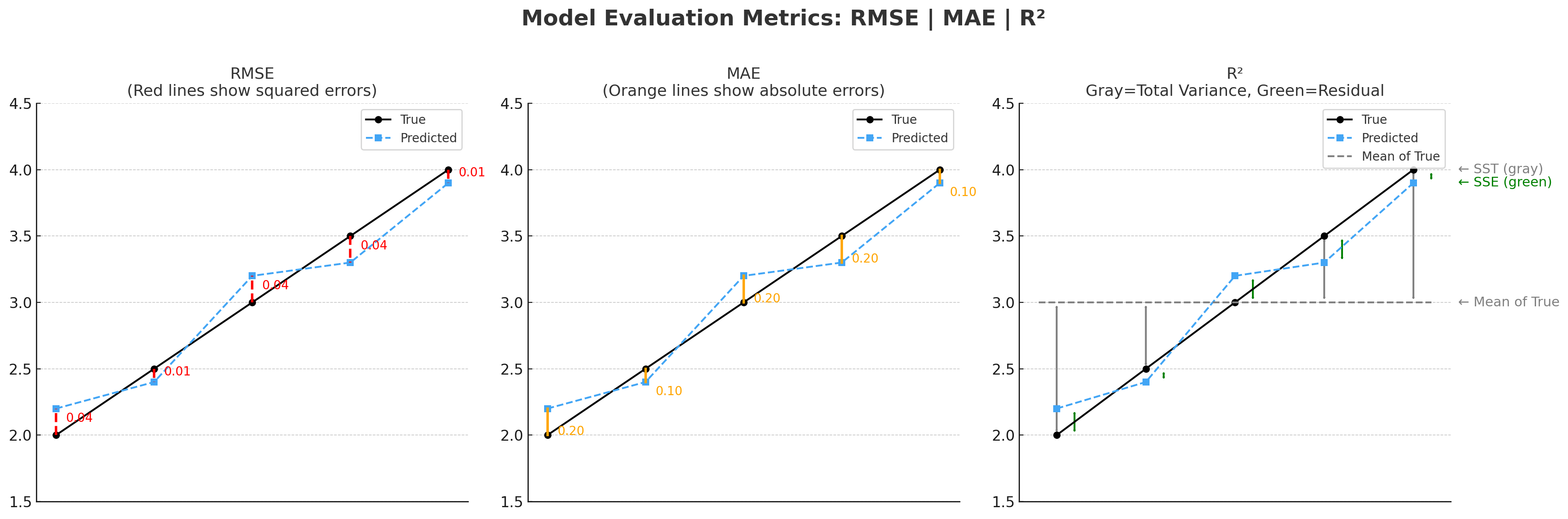

Loss Function: Measuring the Error

The loss function is a mathematical expression that quantifies how far off the model’s predictions are from the actual values. It acts as a feedback mechanism—telling the network how well or poorly it’s performing.

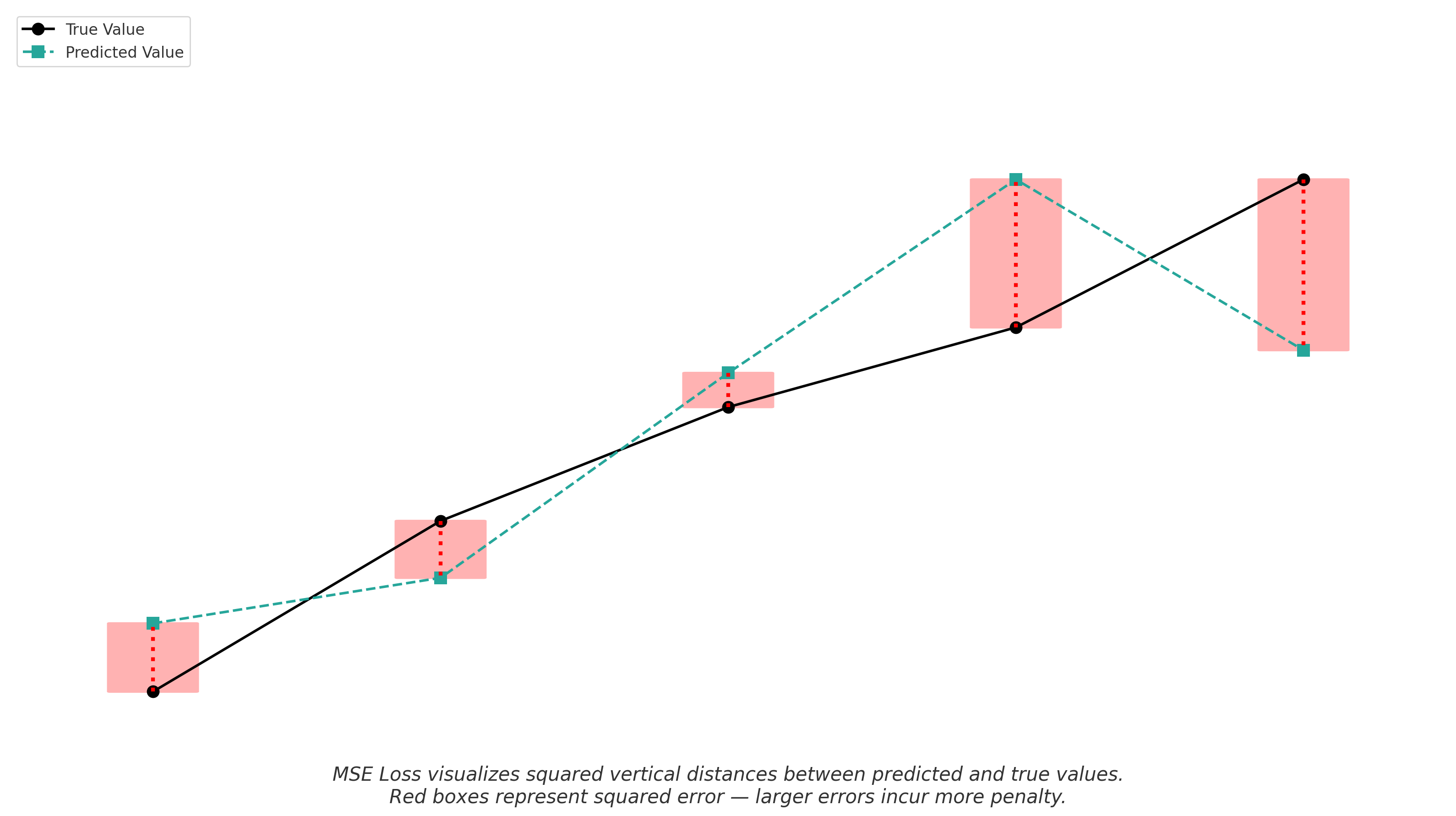

In regression tasks like solubility prediction, a common loss function is Mean Squared Error (MSE):

\[\text{MSE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (\hat{y}_i - y_i)^2\]Where:

- $\hat{y}_i$ is the predicted solubility

- $y_i$ is the true solubility

- $n$ is the number of samples

MSE penalizes larger errors more severely than smaller ones, which is especially useful in chemical property prediction where large prediction errors can have significant consequences.

Gradient Descent: Minimizing the Loss

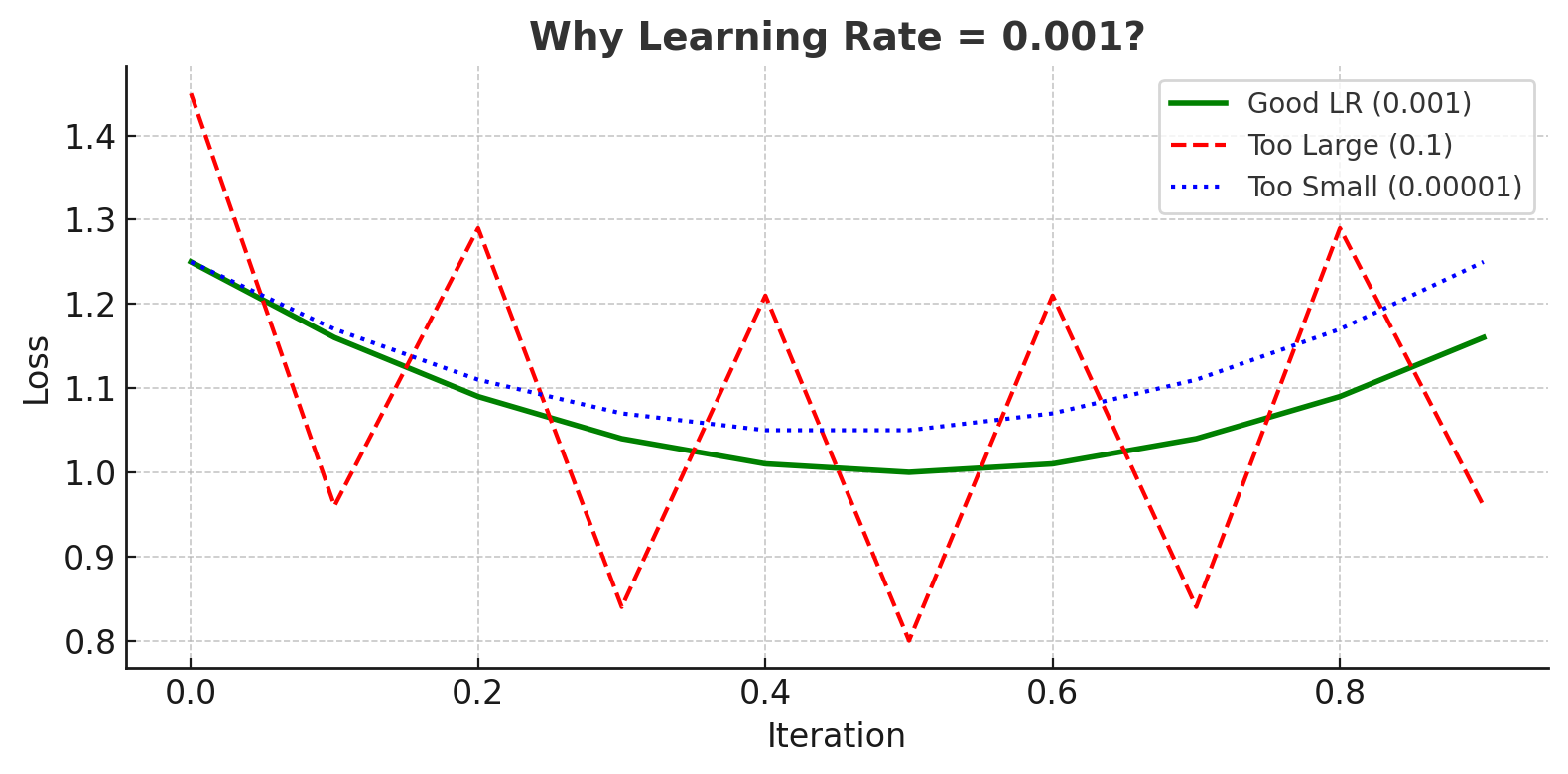

Once the model calculates the loss, it needs to adjust its internal weights to reduce that loss. This optimization process is called gradient descent.

Gradient descent updates the model’s weights in the opposite direction of the gradient of the loss function:

\[w_{\text{new}} = w_{\text{old}} - \alpha \cdot \frac{\partial \text{Loss}}{\partial w}\]Where:

- $w$ is a weight in the network

- $\alpha$ is the learning rate, a small scalar that determines the step size

This iterative update helps the model gradually “descend” toward a configuration that minimizes the prediction error.

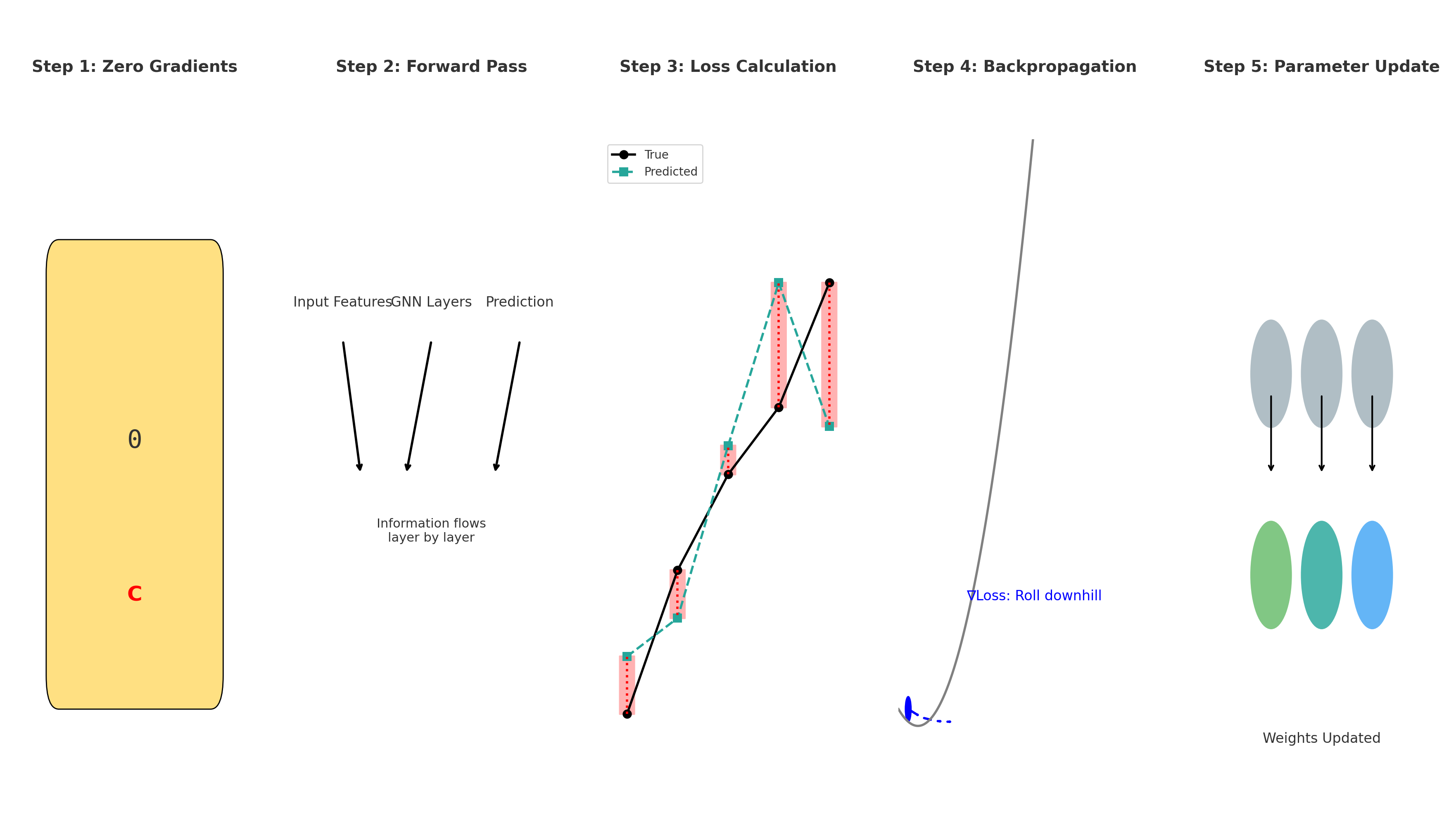

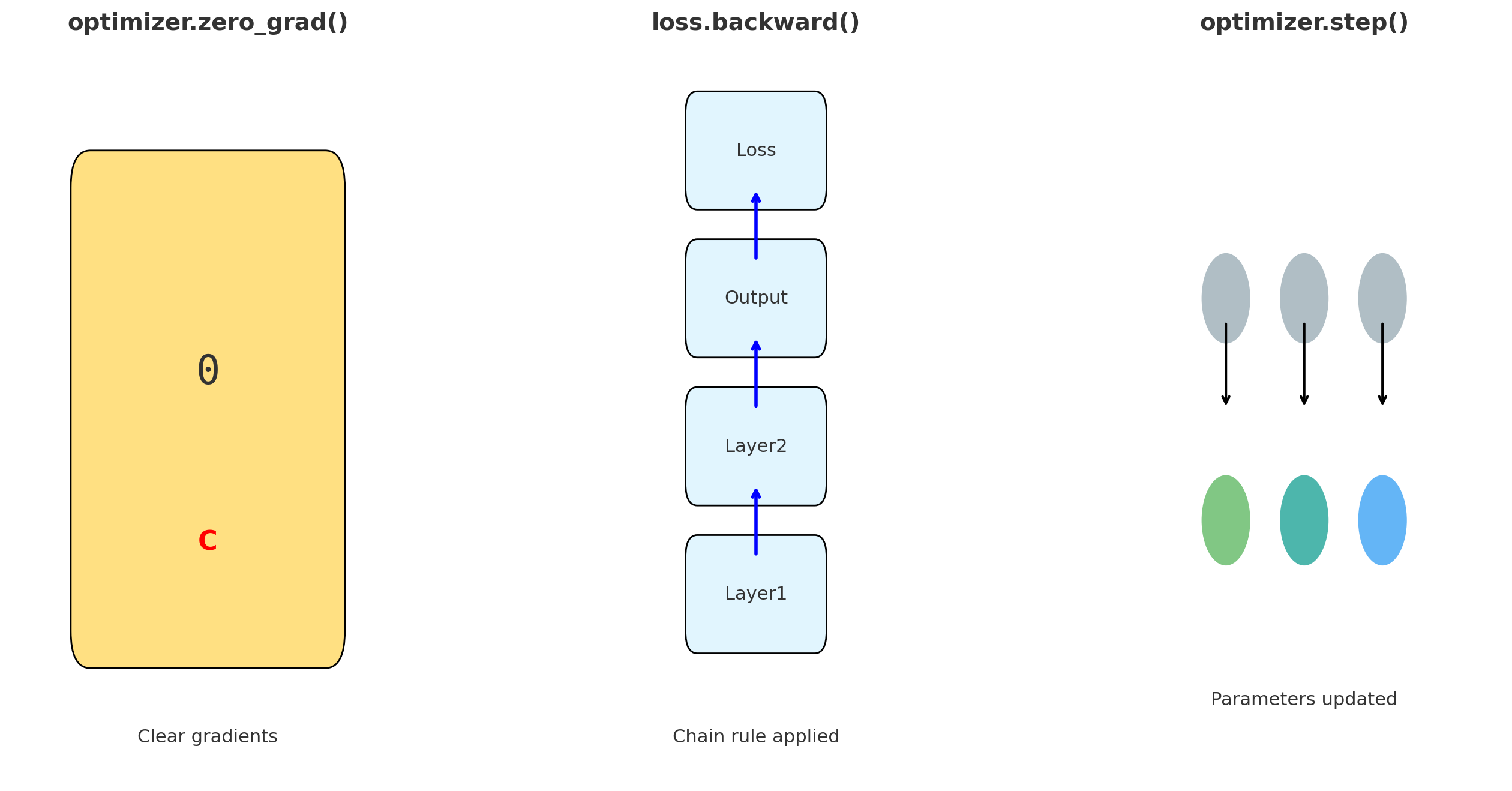

Backpropagation: Updating the Network

Backpropagation is the algorithm that computes how to adjust the weights.

- It begins by computing the prediction and measuring the loss.

- Then, it calculates how much each neuron contributed to the final error by applying the chain rule from calculus.

- Finally, it adjusts all weights by propagating the error backward from the output layer to the input layer.

Over time, the network becomes better at associating input features with the correct output properties.

Intuition for Chemists

Think of a chemist optimizing a synthesis route. After a failed reaction, they adjust parameters (temperature, solvent, reactants) based on what went wrong. With enough trials and feedback, they achieve better yields.

A neural network does the same—after each “trial” (training pass), it adjusts its internal settings (weights) to improve its “yield” (prediction accuracy) the next time.

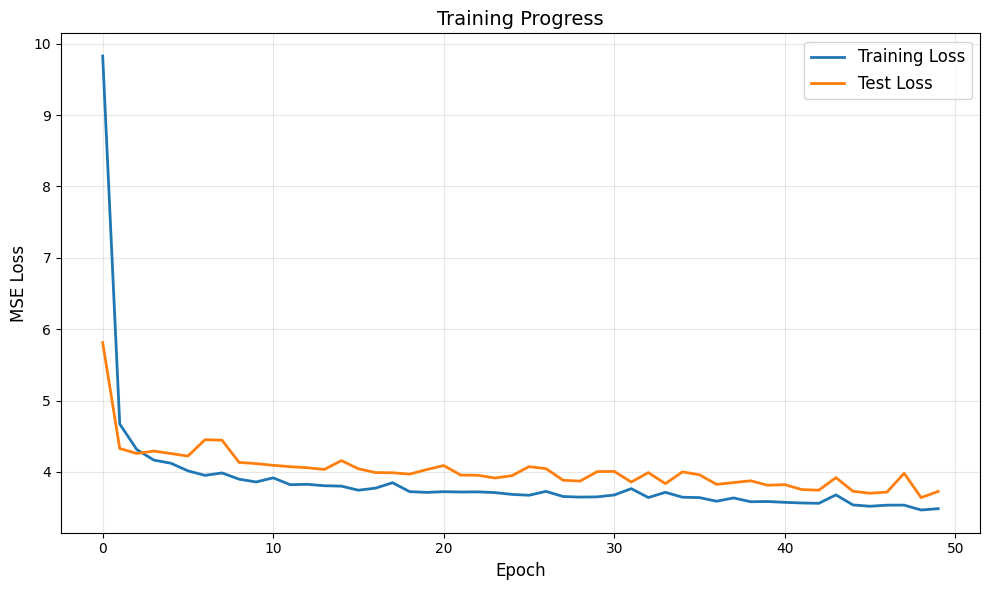

Visualizing Loss Reduction During Training

This code demonstrates how a simple neural network learns over time by minimizing error through backpropagation and gradient descent. It also visualizes the loss curve to help you understand how training progresses.

# 3.2.3 Example: Visualizing Loss Reduction During Training

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from tensorflow.keras.models import Sequential

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Dense

# Simulated training data: [molecular_weight, logP, rotatable_bonds]

X_train = np.array([

[350.2, 3.3, 5],

[275.4, 1.8, 4],

[125.7, 0.2, 1],

[300.1, 2.5, 3],

[180.3, 0.5, 2]

])

# Simulated solubility labels (normalized between 0 and 1)

y_train = np.array([0.42, 0.63, 0.91, 0.52, 0.86])

# Define a simple neural network

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(10, input_dim=3, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')) # Regression output

# Compile the model using MSE (Mean Squared Error) loss

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='mean_squared_error')

# Train the model and record loss values

history = model.fit(X_train, y_train, epochs=100, verbose=0)

# Plot the training loss over time

plt.plot(history.history['loss'])

plt.title('Loss Reduction During Training')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Loss (MSE)')

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

This example demonstrates:

- How the network calculates and minimizes the loss function (MSE)

- How backpropagation adjusts weights over time

- How loss consistently decreases with each epoch

Practice Problem: Observe the Learning Curve

Reinforce the concepts of backpropagation and gradient descent by modifying the model to exaggerate or dampen learning behavior.

- Change the optimizer from “adam” to “sgd” and observe how the loss reduction changes.

- Add validation_split=0.2 to model.fit() to visualize both training and validation loss.

- Plot both loss curves using matplotlib.

# Add validation and switch optimizer

model.compile(optimizer='sgd', loss='mean_squared_error')

history = model.fit(X_train, y_train, epochs=100, validation_split=0.2, verbose=0)

# Plot training and validation loss

plt.plot(history.history['loss'], label='Training Loss')

plt.plot(history.history['val_loss'], label='Validation Loss')

plt.title('Training vs Validation Loss')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

You should observe:

- Slower convergence when using SGD vs. Adam.

- Validation loss potentially diverging if overfitting begins.

3.2.4 Activation Functions

Completed and Compiled Code: Click Here

Activation functions are a key component of neural networks that allow them to model complex, non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs. Without activation functions, no matter how many layers we add, a neural network would essentially behave like a linear model. For chemists, this would mean failing to capture the non-linear relationships between molecular descriptors and properties such as solubility, reactivity, or binding affinity.

What Is an Activation Function?

An activation function is applied to the output of each neuron in a hidden layer. It determines whether that neuron should “fire” (i.e., pass information to the next layer) and to what degree.

Think of it like a valve in a chemical reaction pathway: the valve can allow the signal to pass completely, partially, or not at all—depending on the condition (input value). This gating mechanism allows neural networks to build more expressive models that can simulate highly non-linear chemical behavior.

Common Activation Functions (with Intuition)

Here are the most widely used activation functions and how you can interpret them in chemical modeling contexts:

1. ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit)

\[\text{ReLU}(x) = \max(0,x)\]Behavior: Passes positive values as-is; blocks negative ones.

Analogy: A pH-dependent gate that opens only if the environment is basic (positive).

Use: Fast to compute; ideal for hidden layers in large models.

2. Sigmoid

\[\text{Sigmoid}(x) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}}\]Behavior: Maps input to a value between 0 and 1.

Analogy: Represents probability or confidence — useful when you want to interpret the output as “likelihood of solubility” or “chance of toxicity”.

Use: Often used in the output layer for binary classification.

3. Tanh (Hyperbolic Tangent)

\[\tanh(x) = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{e^x + e^{-x}}\]Behavior: Outputs values between -1 and 1, centered around 0.

Analogy: Models systems with directionality — such as positive vs. negative binding affinity.

Use: Sometimes preferred over sigmoid in hidden layers.

Why Are They Important

Without activation functions, neural networks would be limited to computing weighted sums—essentially doing linear algebra. This would be like trying to model the melting point of a compound using only molecular weight: too simplistic for real-world chemistry.

Activation functions allow networks to “bend” input-output mappings, much like how a catalyst changes the energy profile of a chemical reaction.

Comparing ReLU and Sigmoid Activation Functions

This code visually compares how ReLU and Sigmoid behave across a range of inputs. Understanding the shapes of these activation functions helps chemists choose the right one for a neural network layer depending on the task (e.g., regression vs. classification).

# 3.2.4 Example: Comparing ReLU vs Sigmoid Activation Functions

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define ReLU and Sigmoid activation functions

def relu(x):

return np.maximum(0, x)

def sigmoid(x):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-x))

# Input range

x = np.linspace(-10, 10, 500)

# Compute function outputs

relu_output = relu(x)

sigmoid_output = sigmoid(x)

# Plot the functions

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(x, relu_output, label='ReLU', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(x, sigmoid_output, label='Sigmoid', linewidth=2)

plt.axhline(0, color='gray', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5)

plt.axvline(0, color='gray', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5)

plt.title('Activation Function Comparison: ReLU vs Sigmoid')

plt.xlabel('Input (x)')

plt.ylabel('Activation Output')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

This example demonstrates:

- ReLU outputs 0 for any negative input and increases linearly for positive inputs. This makes it ideal for deep layers in large models where speed and sparsity are priorities.

- Sigmoid smoothly maps all inputs to values between 0 and 1. This is useful for binary classification tasks, such as predicting whether a molecule is toxic or not.

- Why this matters in chemistry: Choosing the right activation function can affect whether your neural network correctly learns properties like solubility, toxicity, or reactivity. For instance, sigmoid may be used in the output layer when predicting probabilities, while ReLU is preferred in hidden layers to retain training efficiency.

3.2.5 Training a Neural Network for Chemical Property Prediction

Completed and Compiled Code: Click Here

In the previous sections, we explored how neural networks are structured and how they learn. In this final section, we’ll put everything together by training a neural network on a small dataset of molecules to predict aqueous solubility — a property of significant importance in drug design and formulation.

Rather than using high-level abstractions, we’ll walk through the full training process: from preparing chemical data to building, training, evaluating, and interpreting a neural network model.

Chemical Context

Solubility determines how well a molecule dissolves in water, which affects its absorption and distribution in biological systems. Predicting this property accurately can save time and cost in early drug discovery. By using features like molecular weight, lipophilicity (LogP), and number of rotatable bonds, we can teach a neural network to approximate this property from molecular descriptors.

Step-by-Step Training Example

Goal: Predict normalized solubility values from 3 molecular descriptors:

- Molecular weight

- LogP

- Number of rotatable bonds

# 3.2.5 Example: Training a Neural Network for Solubility Prediction

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from tensorflow.keras.models import Sequential

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Dense

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

# Step 1: Simulated chemical data

X = np.array([

[350.2, 3.3, 5],

[275.4, 1.8, 4],

[125.7, 0.2, 1],

[300.1, 2.5, 3],

[180.3, 0.5, 2],

[410.0, 4.1, 6],

[220.1, 1.2, 3],

[140.0, 0.1, 1]

])

y = np.array([0.42, 0.63, 0.91, 0.52, 0.86, 0.34, 0.70, 0.95]) # Normalized solubility

# Step 2: Normalize features using MinMaxScaler

scaler = MinMaxScaler()

X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X)

# Step 3: Train-test split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_scaled, y, test_size=0.25, random_state=42)

# Step 4: Build the neural network

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(16, input_dim=3, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(8, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')) # Output layer for regression (normalized range)

# Step 5: Compile and train

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='mean_squared_error')

history = model.fit(X_train, y_train, epochs=100, verbose=0)

# Step 6: Evaluate performance

loss = model.evaluate(X_test, y_test, verbose=0)

print(f"Test Loss (MSE): {loss:.4f}")

# Step 7: Plot training loss

plt.plot(history.history['loss'])

plt.title("Training Loss Over Epochs")

plt.xlabel("Epoch")

plt.ylabel("Loss (MSE)")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

Interpreting the Results

- The network gradually learns to predict solubility based on three molecular features.

- The loss value shows the mean squared error on the test set—lower values mean better predictions.

- The loss curve demonstrates whether the model is converging (flattening loss) or struggling (oscillating loss).

Summary

This section demonstrated how a basic neural network can be trained on molecular descriptors to predict solubility. While our dataset was small and artificial, the same principles apply to real-world cheminformatics datasets.

You now understand:

- How to process input features from molecules

- How to build and train a simple feedforward neural network

- How to interpret loss, predictions, and model performance

This hands-on foundation prepares you to tackle more complex models like convolutional and graph neural networks in the next sections.

Section 3.2 – Quiz Questions

1) Factual Questions

Question 1

Which of the following best describes the role of the hidden layers in a neural network predicting chemical properties?

A. They store the molecular structure for visualization.

B. They transform input features into increasingly abstract representations.

C. They calculate the final solubility or toxicity score directly.

D. They normalize the input data before processing begins.

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: B▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Hidden layers apply weights, biases, and activation functions to extract increasingly complex patterns (e.g., substructures, steric hindrance) from the input molecular data.Question 2

Suppose you’re predicting aqueous solubility using a neural network. Which activation function in the hidden layers would be most suitable to introduce non-linearity efficiently, especially with large chemical datasets?

A. Softmax

B. Linear

C. ReLU

D. Sigmoid

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: ReLU is widely used in hidden layers for its computational efficiency and ability to handle vanishing gradient problems in large datasets.Question 3

In the context of molecular property prediction, which of the following sets of input features is most appropriate for the input layer of a neural network?

A. IUPAC names and structural diagrams

B. Raw SMILES strings and melting points as text

C. Numerical descriptors like molecular weight, LogP, and rotatable bonds

D. Hand-drawn chemical structures and reaction mechanisms

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Neural networks require numerical input. Molecular descriptors are quantifiable features that encode structural, electronic, and steric properties.Question 4

Your neural network performs poorly on new molecular data but does very well on training data. Which of the following is most likely the cause?

A. The model lacks an output layer

B. The training set contains irrelevant descriptors

C. The network is overfitting due to too many parameters

D. The input layer uses too few neurons

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Overfitting occurs when a model memorizes the training data but fails to generalize. This is common in deep networks with many parameters and not enough regularization or data diversity.2) Conceptual Questions

Question 5

You are building a neural network to predict binary activity (active vs inactive) of molecules based on three features: [Molecular Weight, LogP, Rotatable Bonds].

Which code correctly defines the output layer for this classification task?

A. layers.Dense(1)

B. layers.Dense(1, activation=’sigmoid’)

C. layers.Dense(2, activation=’relu’)

D. layers.Dense(3, activation=’softmax’)

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: B▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: For binary classification, you need a single neuron with a sigmoid activation function to output a probability between 0 and 1.Question 6

Why might a chemist prefer a neural network over a simple linear regression model for predicting molecular toxicity?

A. Neural networks can run faster than linear models.

B. Toxicity is not predictable using any mathematical model.

C. Neural networks can model nonlinear interactions between substructures.

D. Neural networks use fewer parameters and are easier to interpret.

▶ Click to show answer

Correct Answer: C▶ Click to show explanation

Explanation: Chemical toxicity often arises from complex, nonlinear interactions among molecular features—something neural networks can capture but linear regression cannot.3.3 Graph Neural Network

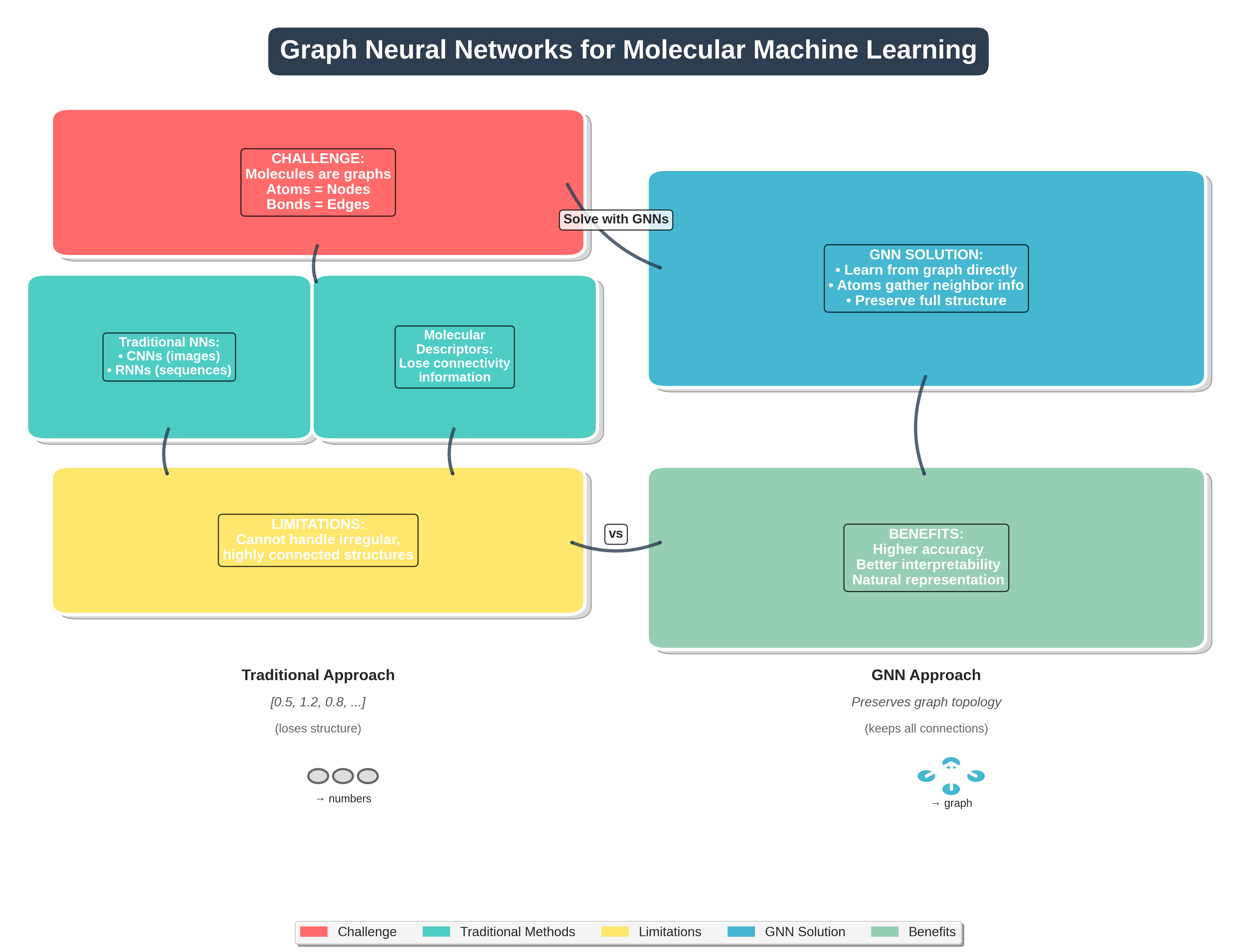

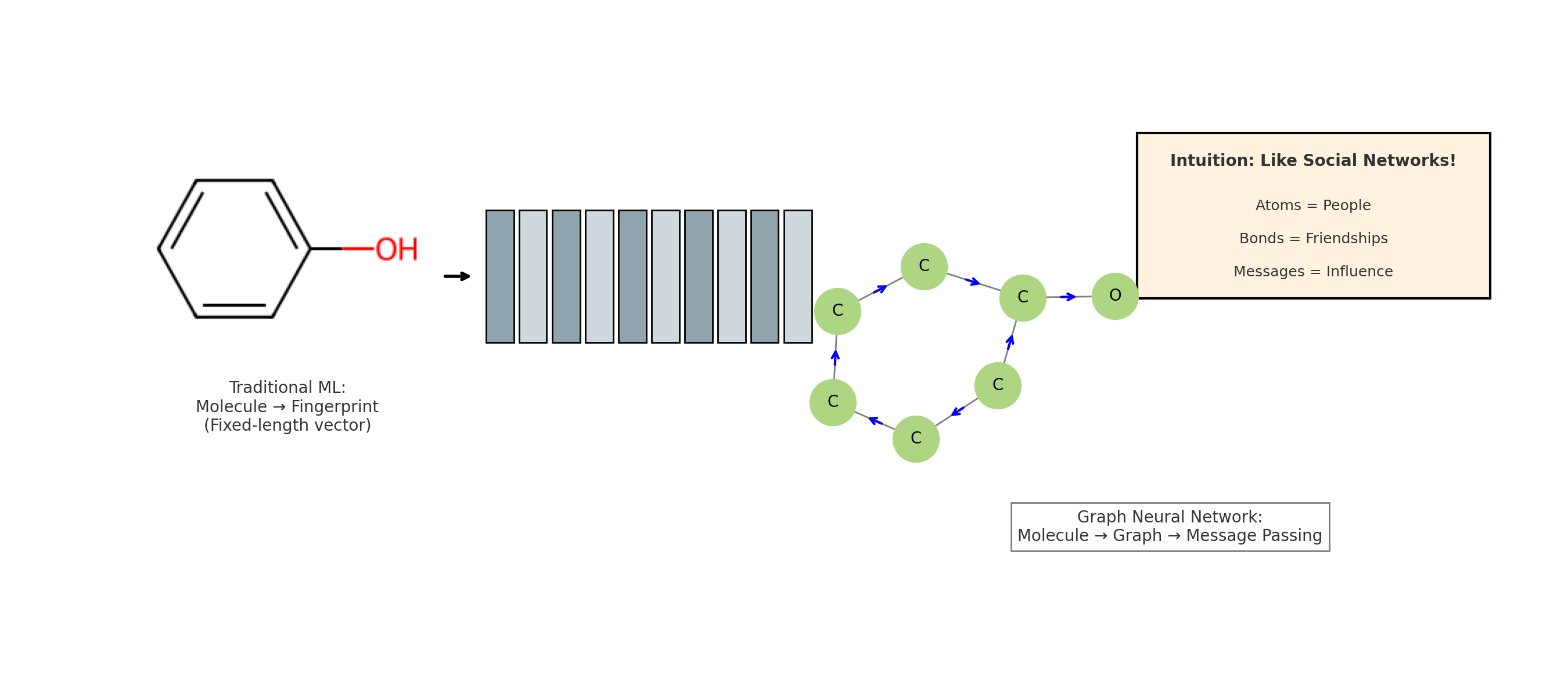

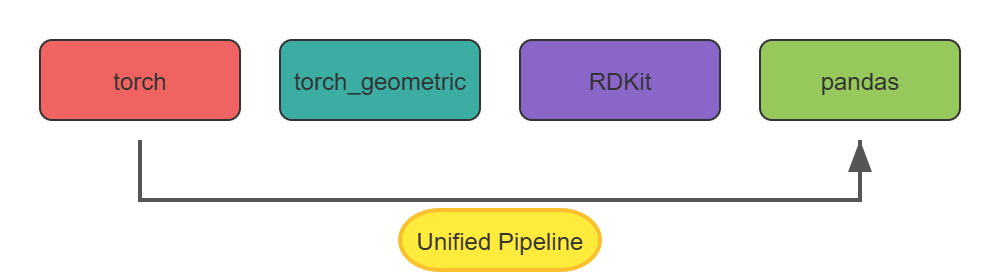

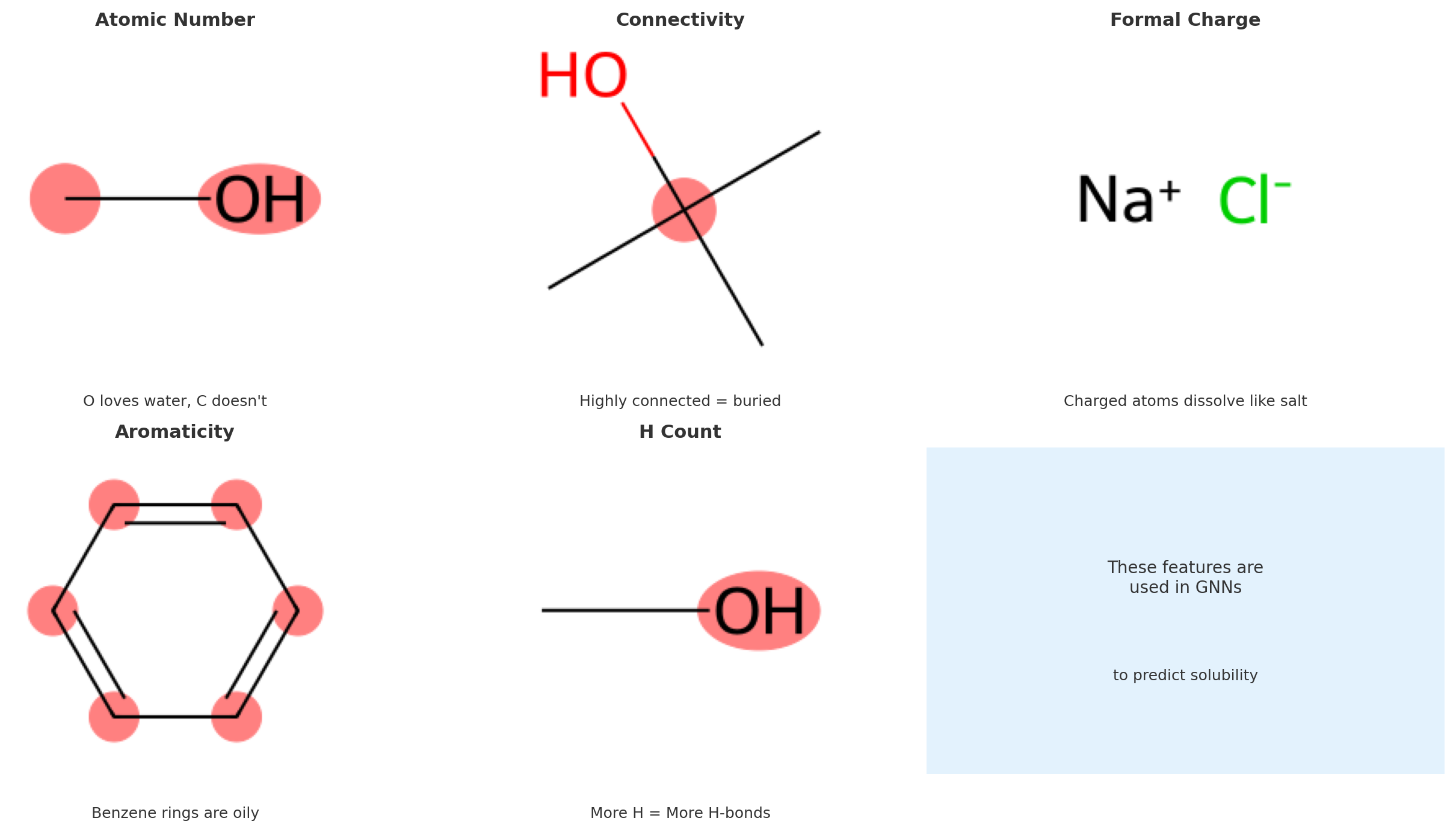

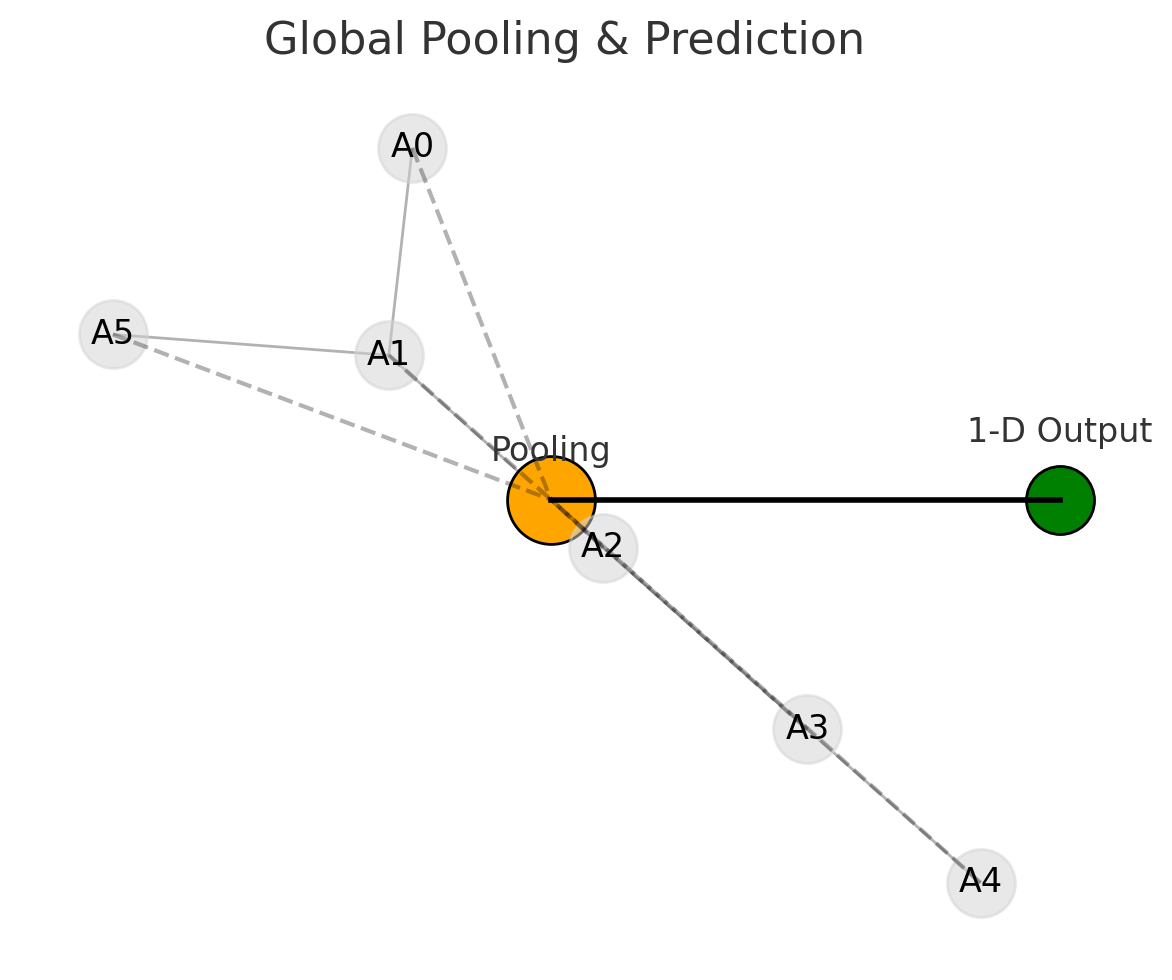

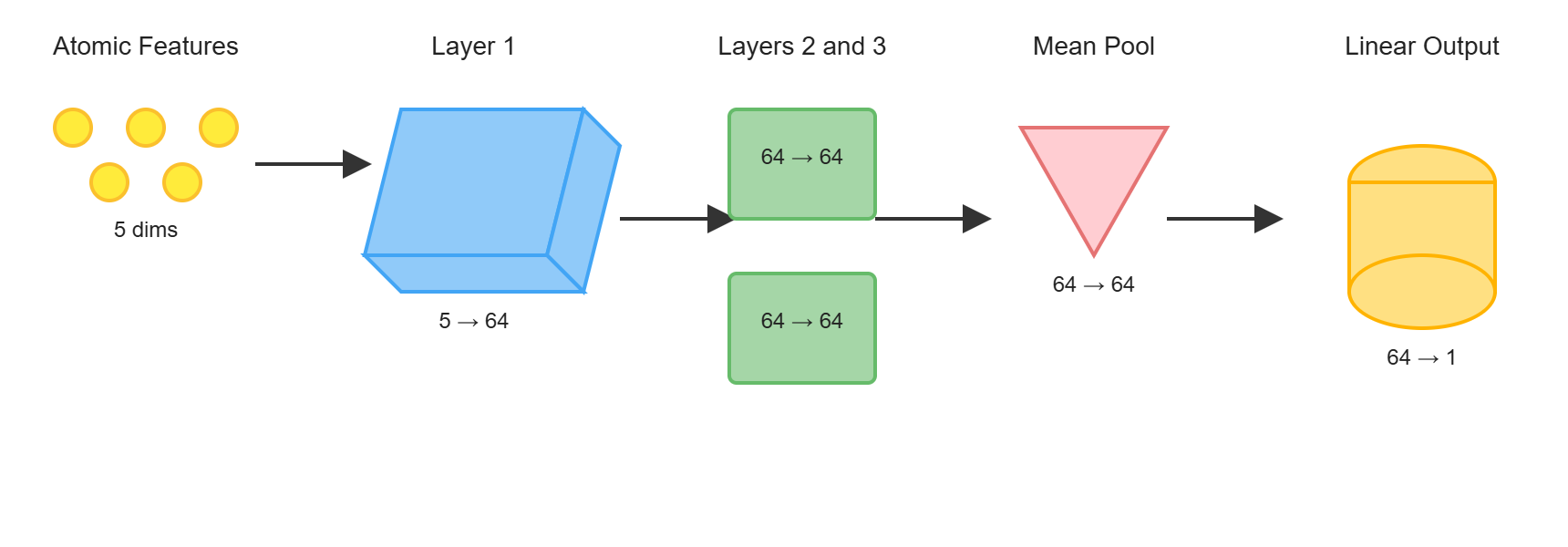

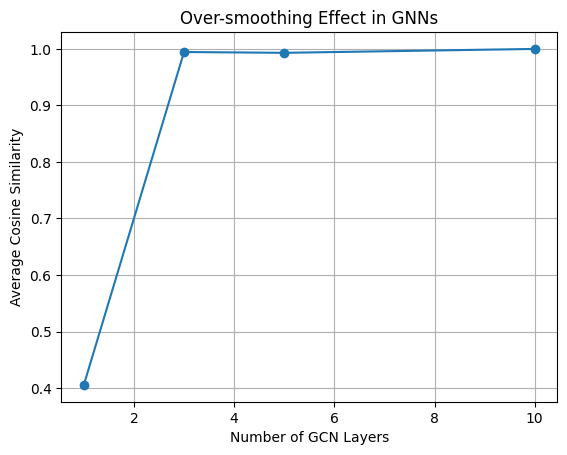

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) offer a new and powerful way to handle molecular machine learning. Traditional neural networks are good at working with fixed-size inputs, such as images or sequences. However, molecules are different in nature. They are best represented as graphs, where atoms are nodes and chemical bonds are edges. This kind of graph structure has always been central in chemistry, appearing in everything from simple Lewis structures to complex reaction pathways. GNNs make it possible for computers to work directly with this kind of data structure.

Unlike images or text, molecules do not follow a regular shape or order. This makes it hard for conventional neural networks to process them effectively. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are designed for image data, and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are built for sequences, but neither is suited to the irregular and highly connected structure of molecules. As a result, older models often fail to capture how atoms are truly linked inside a molecule.

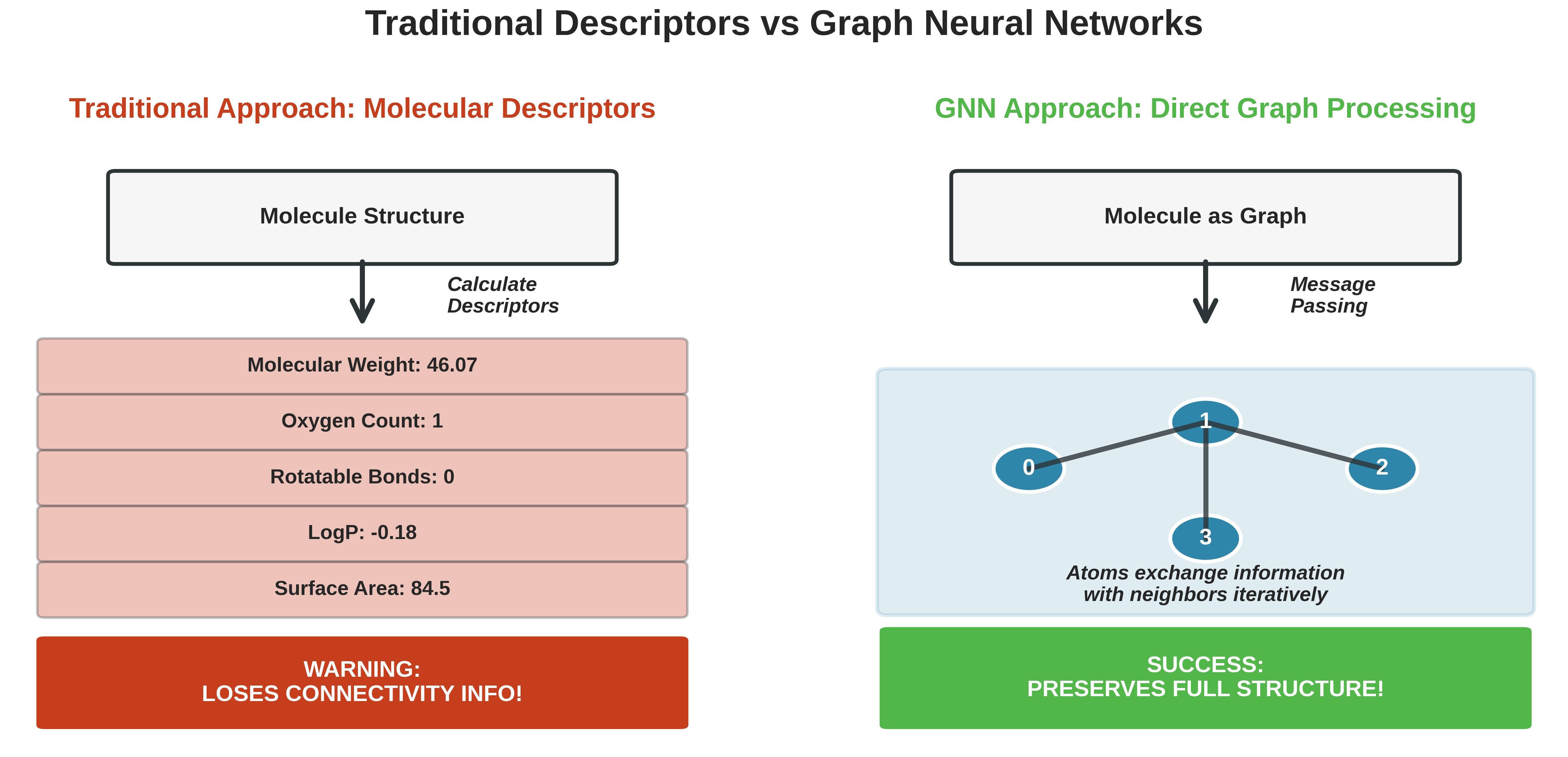

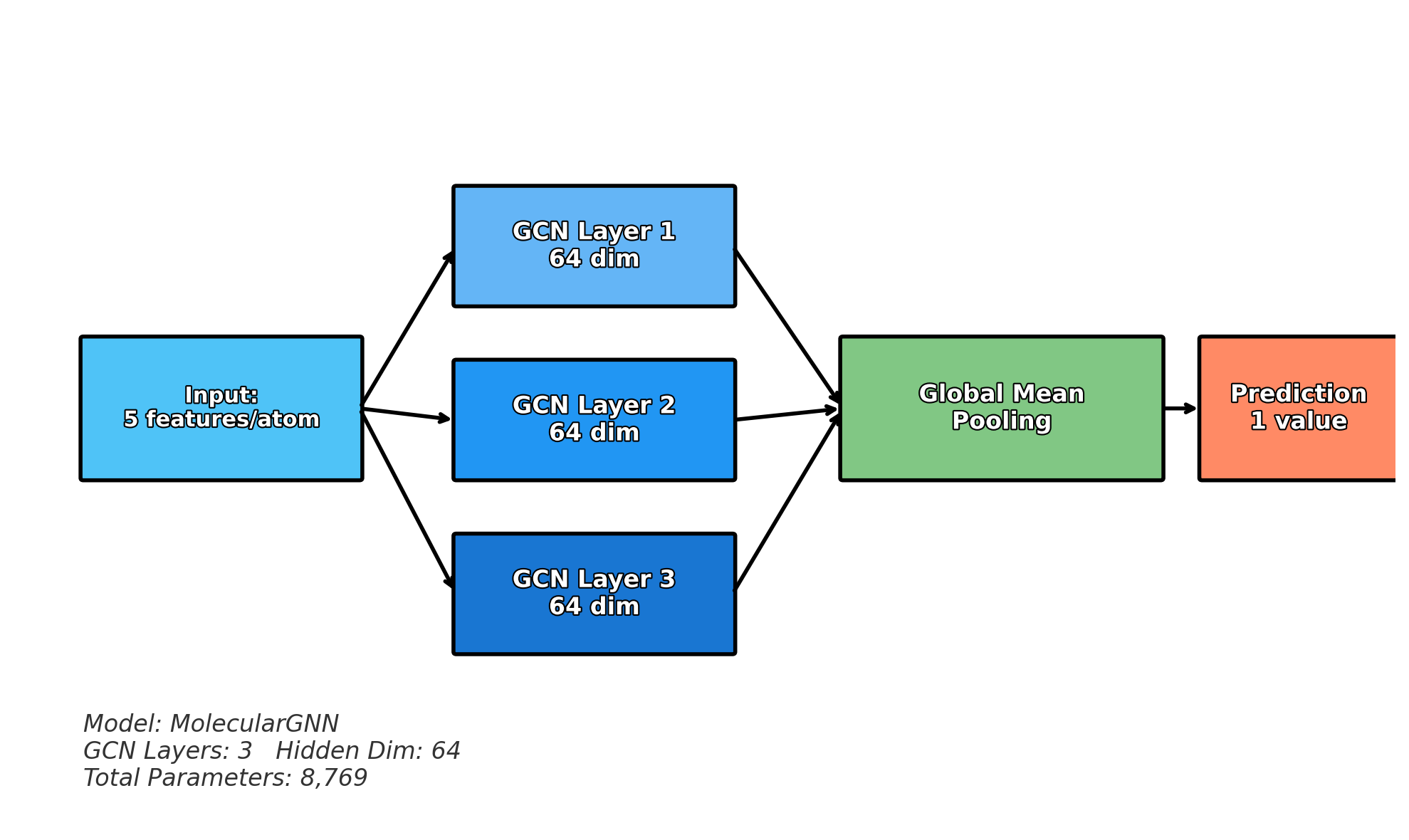

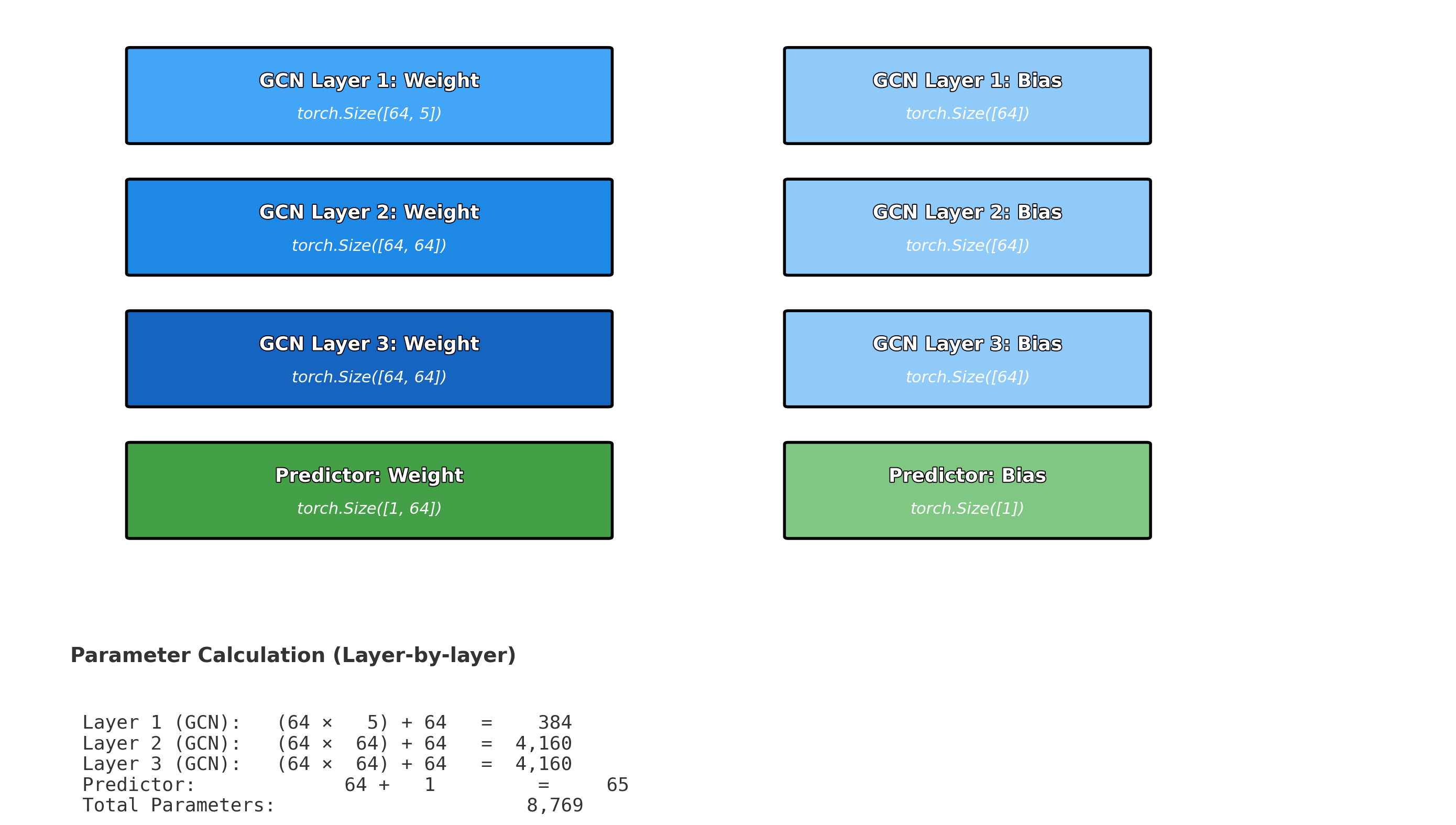

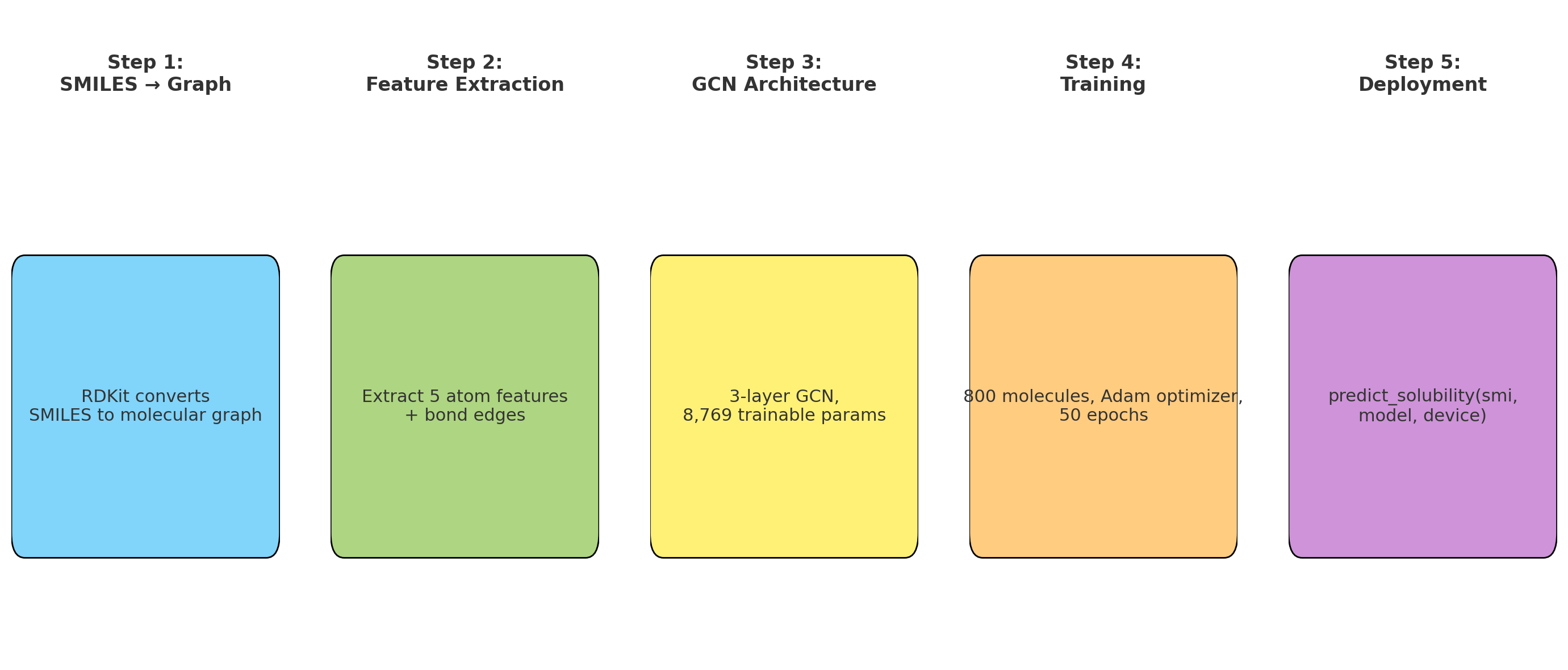

Comparison between traditional neural network approaches and Graph Neural Networks for molecular machine learning. The flowchart illustrates why molecules require graph-based methods and how GNNs preserve structural information that traditional methods lose.

Comparison between traditional neural network approaches and Graph Neural Networks for molecular machine learning. The flowchart illustrates why molecules require graph-based methods and how GNNs preserve structural information that traditional methods lose.

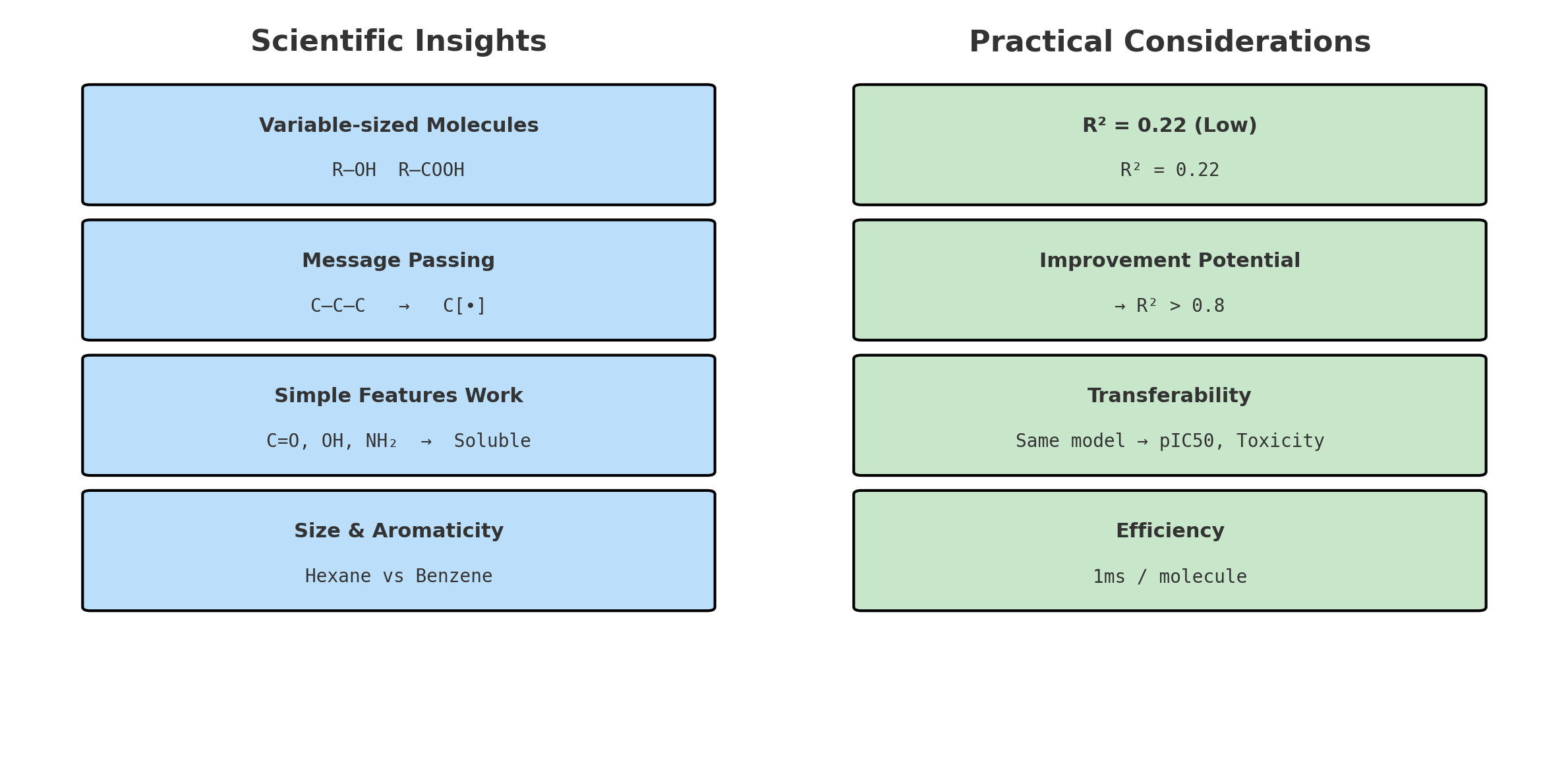

Before GNNs were introduced, chemists used what are known as molecular descriptors. These are numerical features based on molecular structure, such as how many functional groups a molecule has or how its atoms are arranged in space. These descriptors were used as input for machine learning models. However, they often lose important information about the exact way atoms are connected. This loss of detail limits how well the models can predict molecular behavior.

GNNs solve this problem by learning directly from the molecular graph. Instead of relying on handcrafted features, GNNs use the structure itself to learn what matters. Each atom gathers information from its neighbors in the graph, which helps the model understand the molecule as a whole. This approach leads to more accurate predictions and also makes the results easier to interpret.

In short, GNNs allow researchers to build models that reflect the true structure of molecules. They avoid the limitations of older methods by directly using the connections between atoms, offering a more natural and powerful way to predict molecular properties.

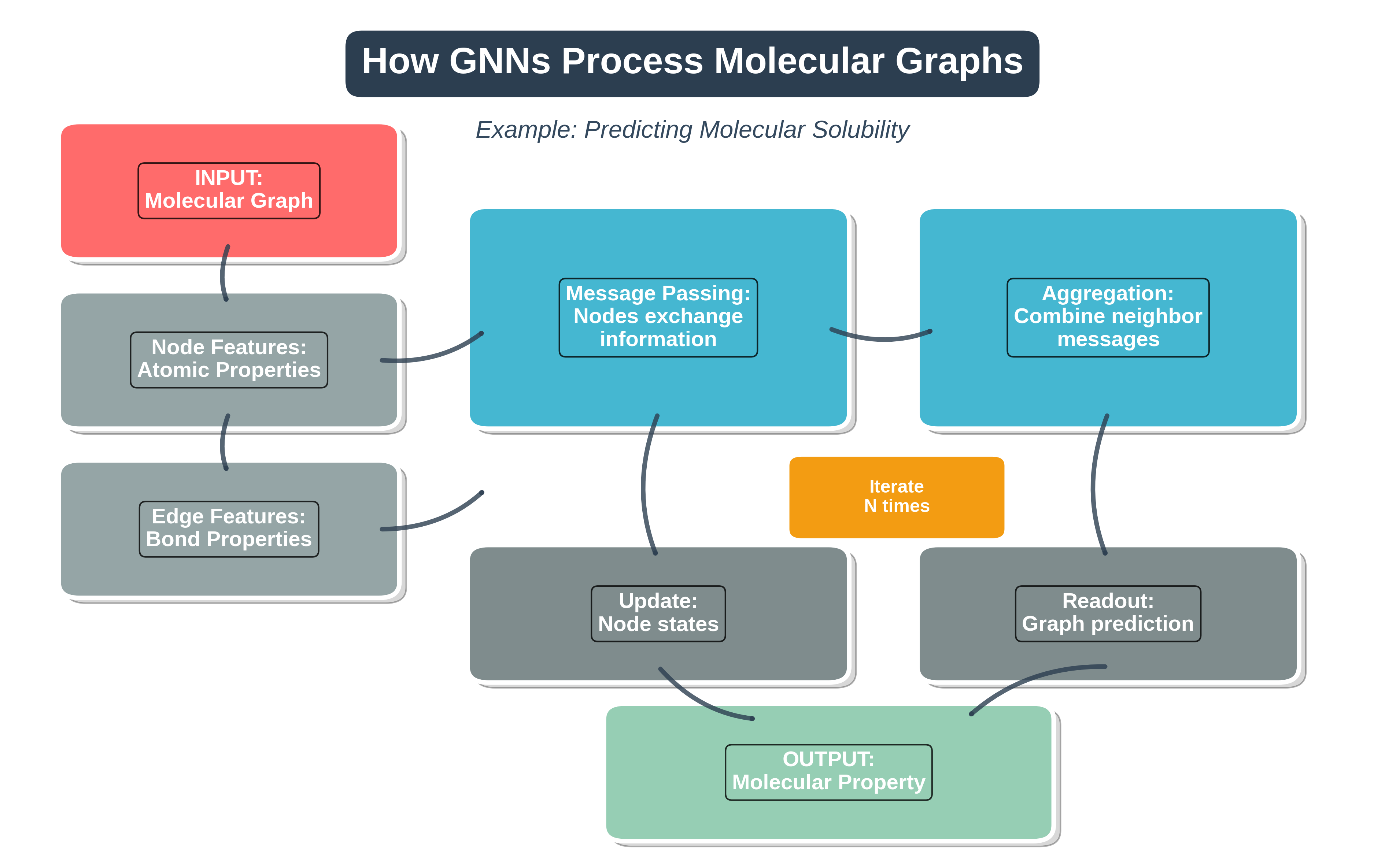

Step-by-step visualization of how Graph Neural Networks process molecular graphs. The pipeline shows the flow from input molecular graph through message passing and aggregation to final property prediction.

Step-by-step visualization of how Graph Neural Networks process molecular graphs. The pipeline shows the flow from input molecular graph through message passing and aggregation to final property prediction.

3.3.1 What Are Graph Neural Networks?

Completed and Compiled Code: Click Here

Why Are Molecules Naturally Graphs?

Let’s start with the most fundamental question: Why do we say molecules are graphs?

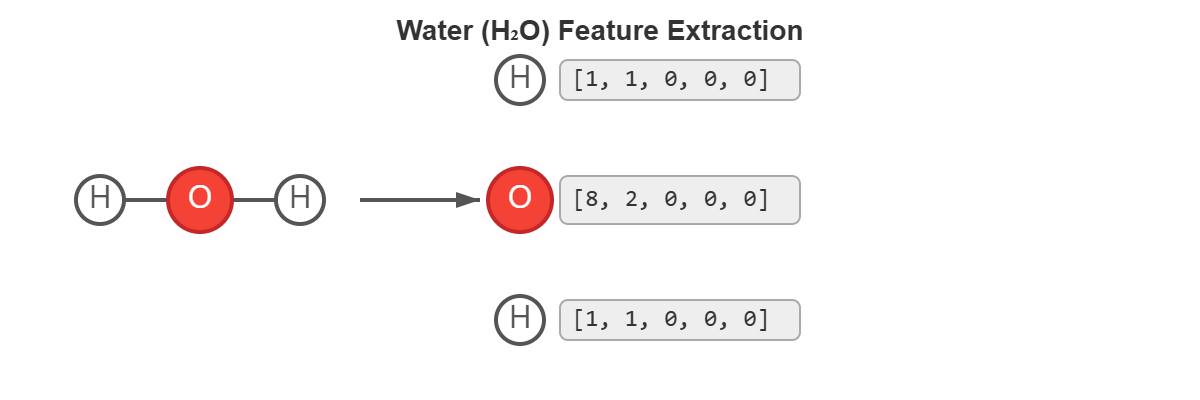

Imagine a water molecule (H₂O). If you’ve taken chemistry, you know it looks like this:

H - O - H

This is already a graph! Let’s break it down:

- Nodes (vertices): The atoms - one oxygen (O) and two hydrogens (H)

- Edges (connections): The chemical bonds - two O-H bonds

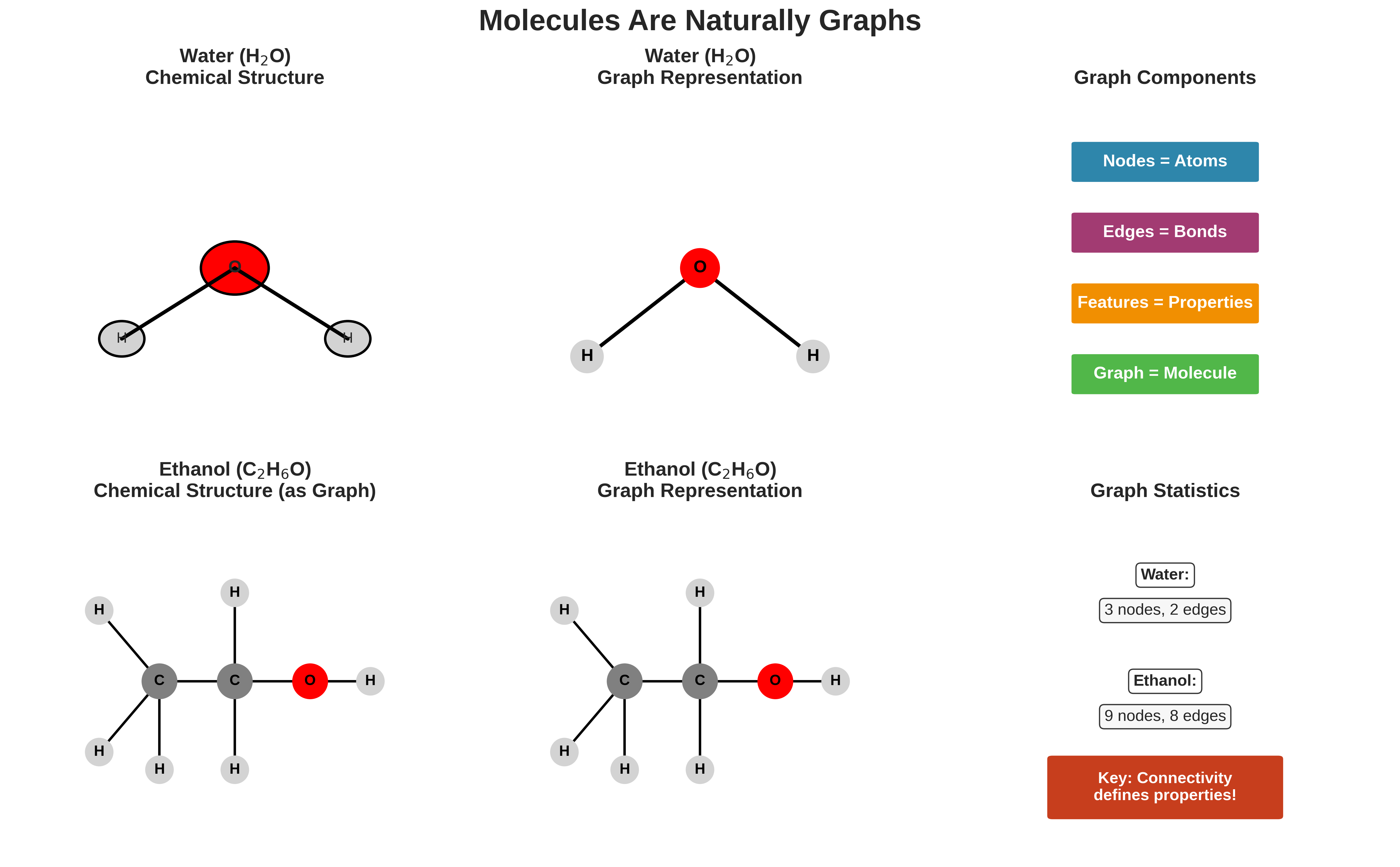

Visualization showing how molecules naturally form graph structures. Water (H₂O) and ethanol (C₂H₆O) are shown in both chemical notation and graph representation, demonstrating that atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

Visualization showing how molecules naturally form graph structures. Water (H₂O) and ethanol (C₂H₆O) are shown in both chemical notation and graph representation, demonstrating that atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

Now consider a slightly more complex molecule - ethanol (drinking alcohol):

H H

| |

H - C-C - O - H

| |

H H

Again, we have a graph:

- 9 nodes: 2 carbons, 1 oxygen, 6 hydrogens

- 8 edges: All the chemical bonds connecting these atoms

Here’s the key insight: A molecule’s properties depend heavily on how its atoms are connected. Water dissolves salt because its bent O-H-O structure creates a polar molecule. Diamond is hard while graphite is soft - both are pure carbon, but connected differently!

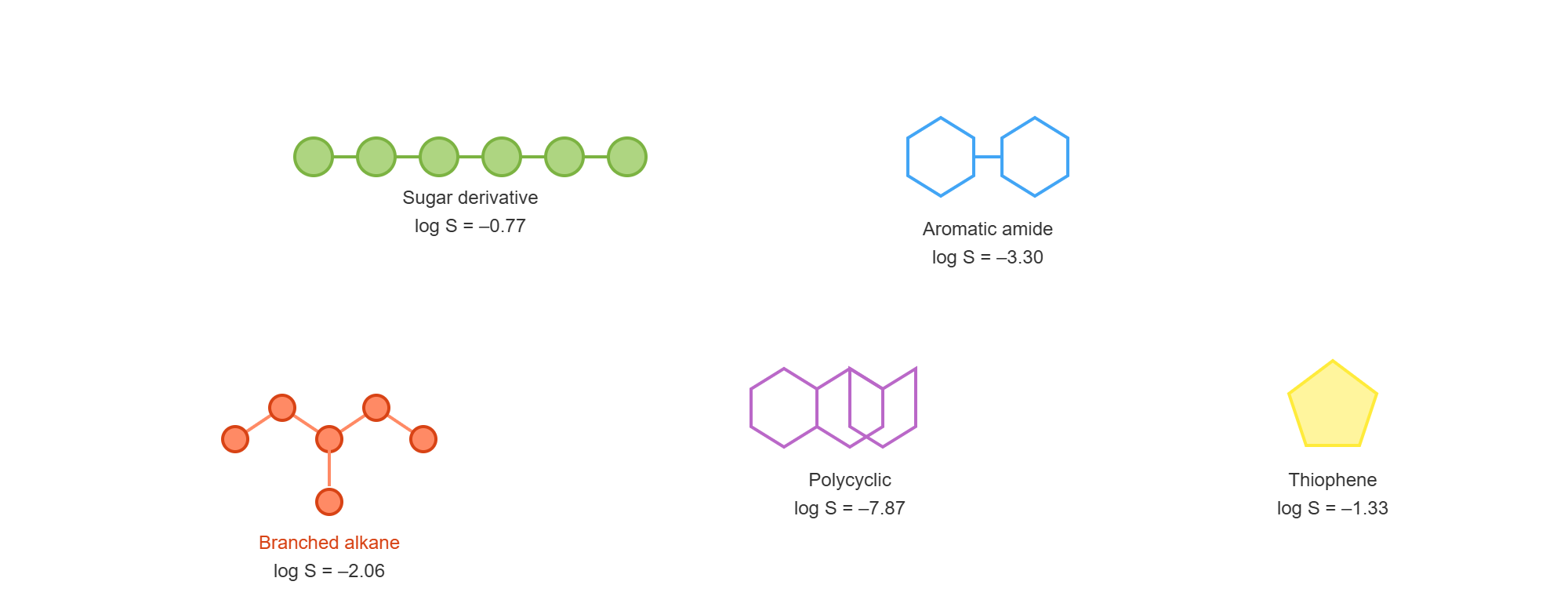

The Molecular Property Prediction Challenge

Before GNNs, how did computers predict molecular properties like solubility, toxicity, or drug effectiveness? Scientists would calculate numerical “descriptors” - features like:

- Molecular weight (sum of all atom weights)

- Number of oxygen atoms

- Number of rotatable bonds

- Surface area

But this approach has a fundamental flaw. Consider these two molecules:

Comparison between traditional molecular descriptors and Graph Neural Networks. Traditional methods lose connectivity information by converting molecules into numerical features, while GNNs preserve the full molecular structure through direct graph processing.

Comparison between traditional molecular descriptors and Graph Neural Networks. Traditional methods lose connectivity information by converting molecules into numerical features, while GNNs preserve the full molecular structure through direct graph processing.

Molecule A: H-O-C-C-C-C-O-H (linear structure)

Molecule B: H-O-C-C-O-H (branched structure)

|

C-C

Traditional descriptors might count:

- Both have 2 oxygens ✓

- Both have similar molecular weights ✓

- Both have OH groups ✓

Yet their properties could be vastly different! The traditional approach loses the connectivity information - it treats molecules as “bags of atoms” rather than structured entities.

Enter Graph Neural Networks

GNNs solve this problem elegantly. They process molecules as they truly are - graphs where:

| Graph Component | Chemistry Equivalent | Example in Ethanol |

|---|---|---|

| Node | Atom | C, C, O, H, H, H, H, H, H |

| Edge | Chemical bond | C-C, C-O, C-H bonds |

| Node features | Atomic properties | Carbon has 4 bonds, Oxygen has 2 |

| Edge features | Bond properties | Single bond, double bond |

| Graph | Complete molecule | The entire ethanol structure |

How GNNs Learn from Molecular Graphs

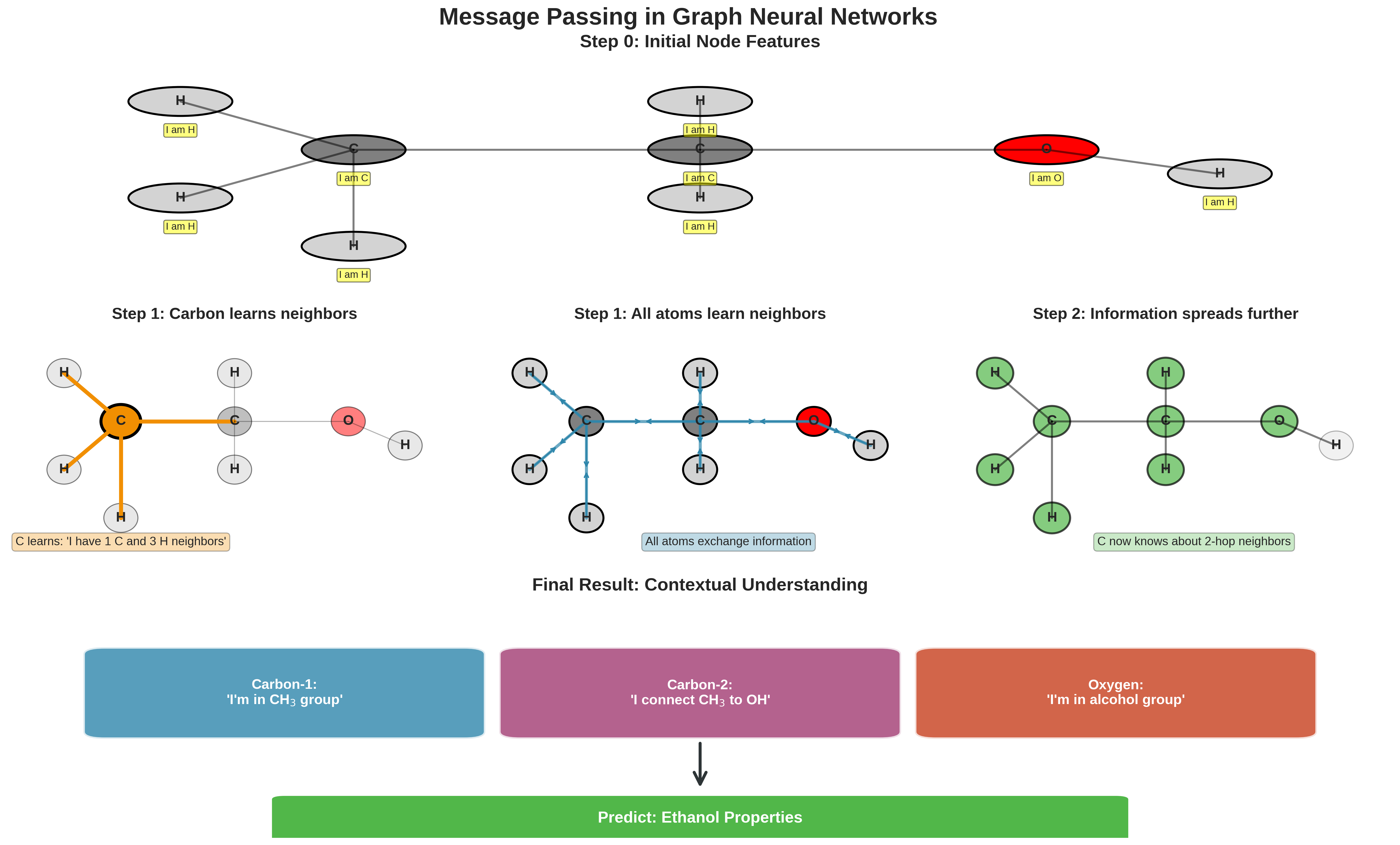

The magic of GNNs lies in message passing - atoms “talk” to their neighbors through bonds. Let’s see how this works step by step:

Step-by-step visualization of the message passing mechanism in GNNs. The figure shows how information propagates through the molecular graph over multiple iterations, allowing each atom to understand its role within the larger molecular context.

Step-by-step visualization of the message passing mechanism in GNNs. The figure shows how information propagates through the molecular graph over multiple iterations, allowing each atom to understand its role within the larger molecular context.

Step 0: Initial State Each atom starts knowing only about itself:

Carbon-1: "I'm carbon with 4 bonds"

Carbon-2: "I'm carbon with 4 bonds"

Oxygen: "I'm oxygen with 2 bonds"

Step 1: First Message Pass Atoms share information with neighbors:

Carbon-1: "I'm carbon connected to another carbon and 3 hydrogens"

Carbon-2: "I'm carbon between another carbon and an oxygen"

Oxygen: "I'm oxygen connected to a carbon and a hydrogen"

Step 2: Second Message Pass Information spreads further:

Carbon-1: "I'm in an ethyl group (CH3CH2-)"

Carbon-2: "I'm the connection point to an OH group"

Oxygen: "I'm part of an alcohol (-OH) group"

After enough message passing, each atom understands its role in the entire molecular structure!

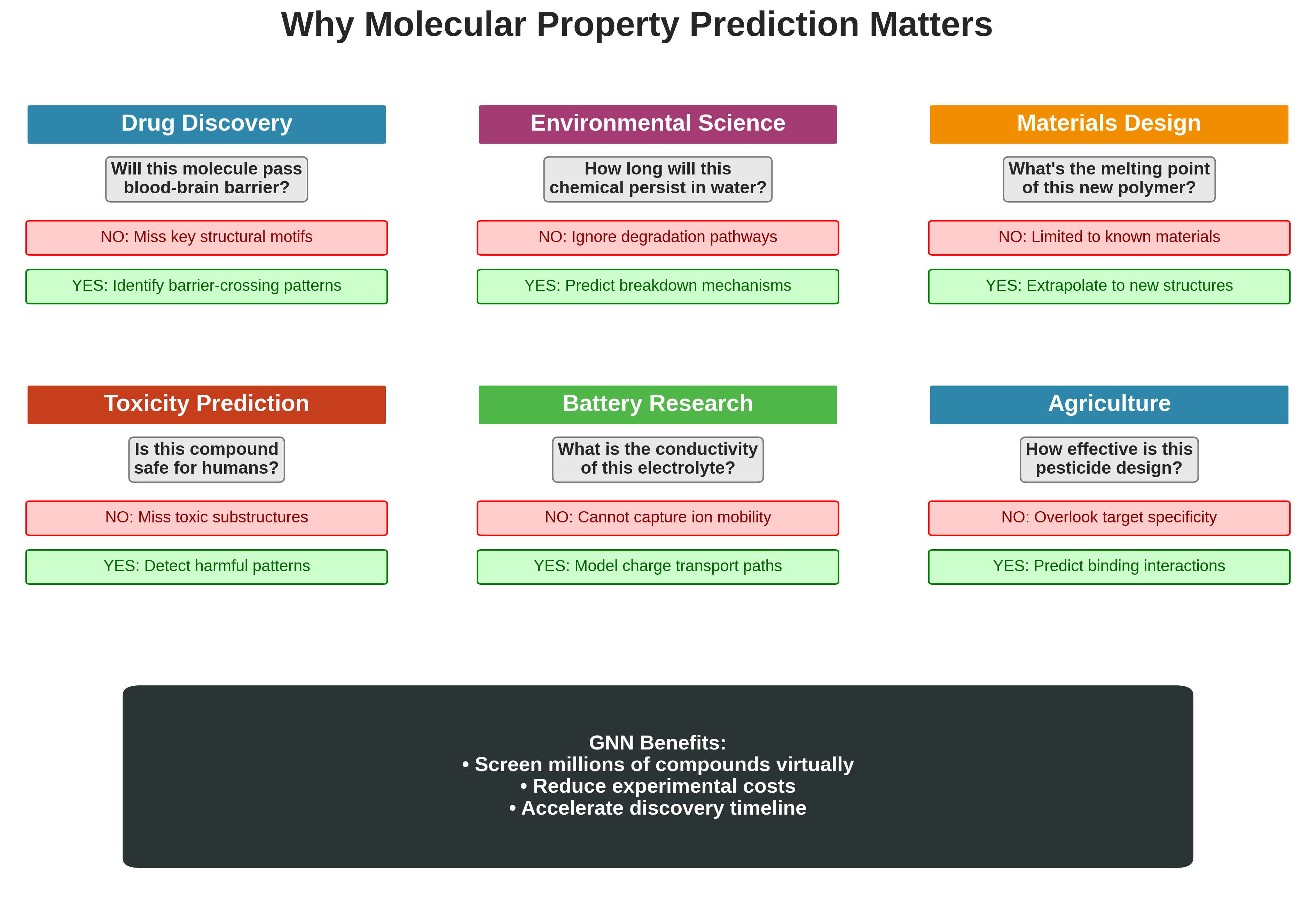

Why Molecular Property Prediction Matters

Molecular property prediction is at the heart of modern drug discovery and materials science. Consider these real-world applications:

Real-world applications of molecular property prediction using GNNs across six domains: drug discovery, environmental science, materials design, toxicity prediction, battery research, and agriculture.

Real-world applications of molecular property prediction using GNNs across six domains: drug discovery, environmental science, materials design, toxicity prediction, battery research, and agriculture.

- Drug Discovery: Will this molecule pass through the blood-brain barrier?

- Environmental Science: How long will this chemical persist in water?

- Materials Design: What’s the melting point of this new polymer?

Traditional experiments to measure these properties are expensive and time-consuming. If we can predict properties from structure alone, we can:

- Screen millions of virtual compounds before synthesizing any

- Identify promising drug candidates faster

- Avoid creating harmful compounds

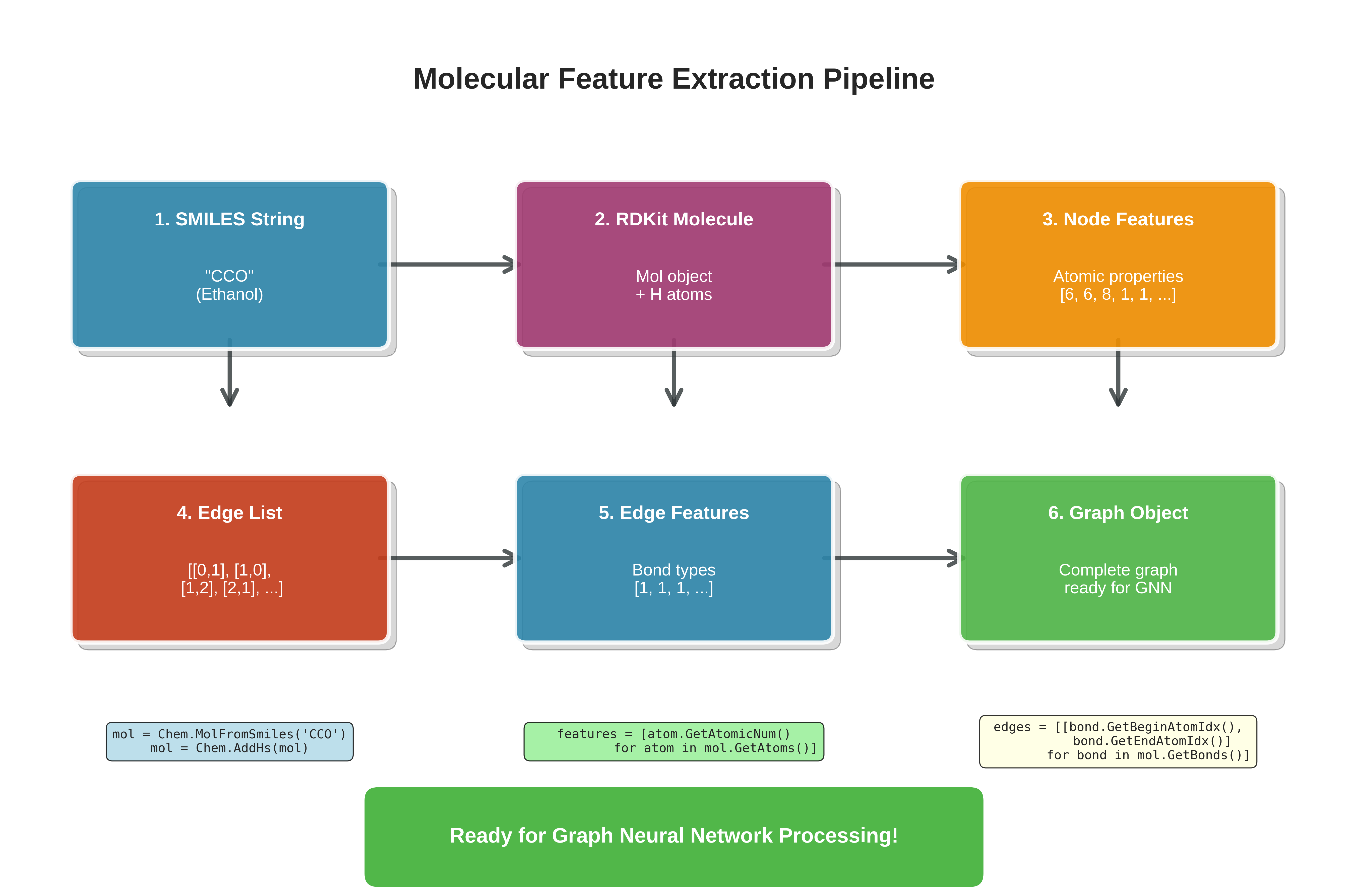

Representing Molecules as Graphs: A Step-by-Step Guide

Let’s implement a simple example to see how we represent molecules as graphs in code.

We’ll walk step-by-step through a basic molecular graph construction pipeline using RDKit, a popular cheminformatics toolkit in Python. You’ll learn how to load molecules, add hydrogens, inspect atoms and bonds, and prepare graph-based inputs for further learning.

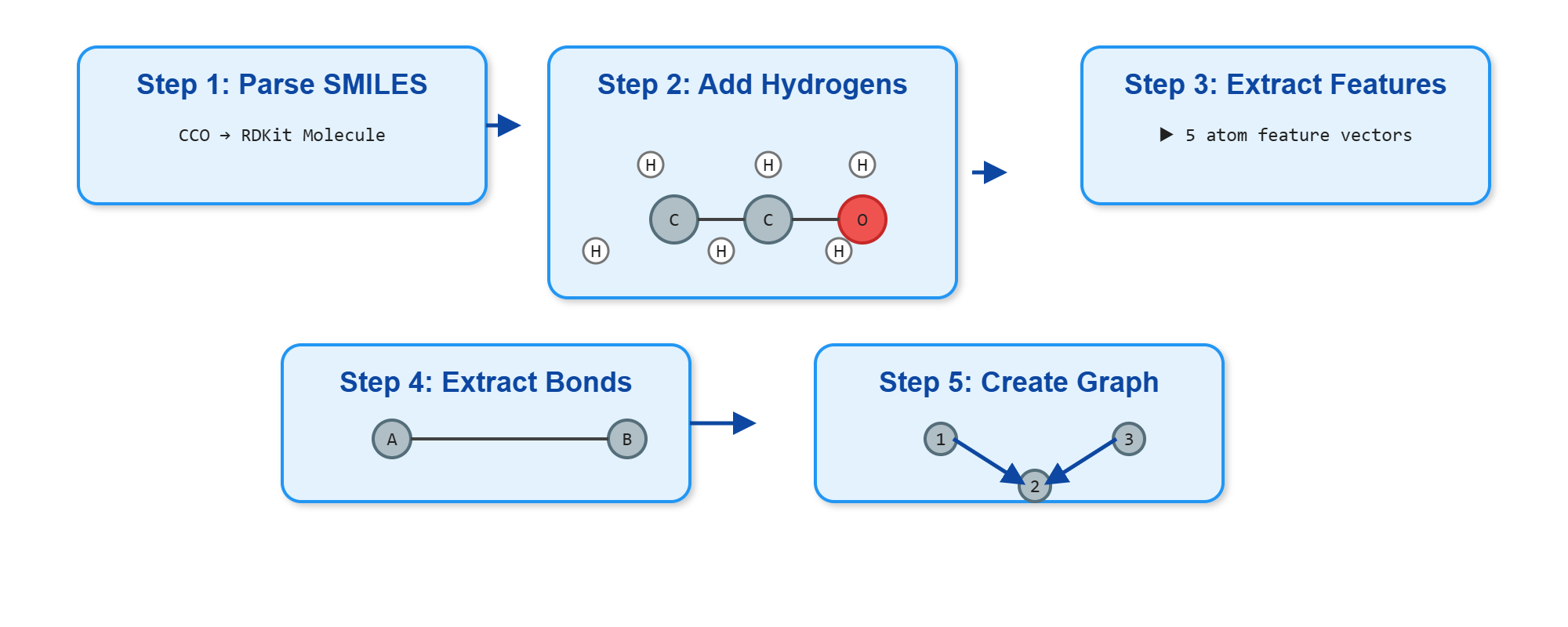

Complete pipeline for converting molecular SMILES strings into graph representations suitable for GNN processing. The workflow shows six stages: from SMILES input through RDKit molecule creation, node/edge feature extraction, to final graph object construction.

Complete pipeline for converting molecular SMILES strings into graph representations suitable for GNN processing. The workflow shows six stages: from SMILES input through RDKit molecule creation, node/edge feature extraction, to final graph object construction.

1. Load a molecule and include hydrogen atoms

To start, we need to load a molecule using RDKit. RDKit provides a function Chem.MolFromSmiles() to create a molecule object from a SMILES string (a standard text representation of molecules). However, by default, hydrogen atoms are not included explicitly in the molecule. To use GNNs effectively, we want all atoms explicitly shown, so we also call Chem.AddHs() to add them in.

Let’s break down the functions we’ll use:

-

Chem.MolFromSmiles(smiles_str): Creates anrdkit.Chem.rdchem.Molobject from a SMILES string. This object represents the molecule internally as atoms and bonds. -

mol.GetNumAtoms(): Returns the number of atoms currently present in the molecule object (by default, RDKit does not include H atoms unless you explicitly add them). -

Chem.AddHs(mol): Returns a new molecule object with explicit hydrogen atoms added to the inputmol.

▶ Click to see code: Basic molecule to graph conversion

from rdkit import Chem

import numpy as np

# Step 1: Create a molecule object from the SMILES string for water ("O" means one oxygen atom)

water = Chem.MolFromSmiles("O")

# Count how many atoms are present (will be 1 — only the oxygen)

print(f"Number of atoms: {water.GetNumAtoms()}") # Output: 1

# Step 2: Add explicit hydrogen atoms

water = Chem.AddHs(water)

# Count again — now we should see 3 atoms (1 O + 2 H)

print(f"Number of atoms with H: {water.GetNumAtoms()}") # Output: 3

- Initial Atom Count: Initially, the molecule object only includes the oxygen atom, as hydrogen atoms are not explicitly represented by default. Therefore,

GetNumAtoms()returns1. - Adding Hydrogen Atoms: After calling

Chem.AddHs(water), the molecule object is updated to include explicit hydrogen atoms. This is essential for a complete representation of the molecule. - Final Atom Count: The final count of atoms is

3, which includes one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. This accurately reflects the molecular structure of water (H₂O).

By explicitly adding hydrogen atoms, we ensure that the molecular graph representation is comprehensive and suitable for further processing in GNNs.

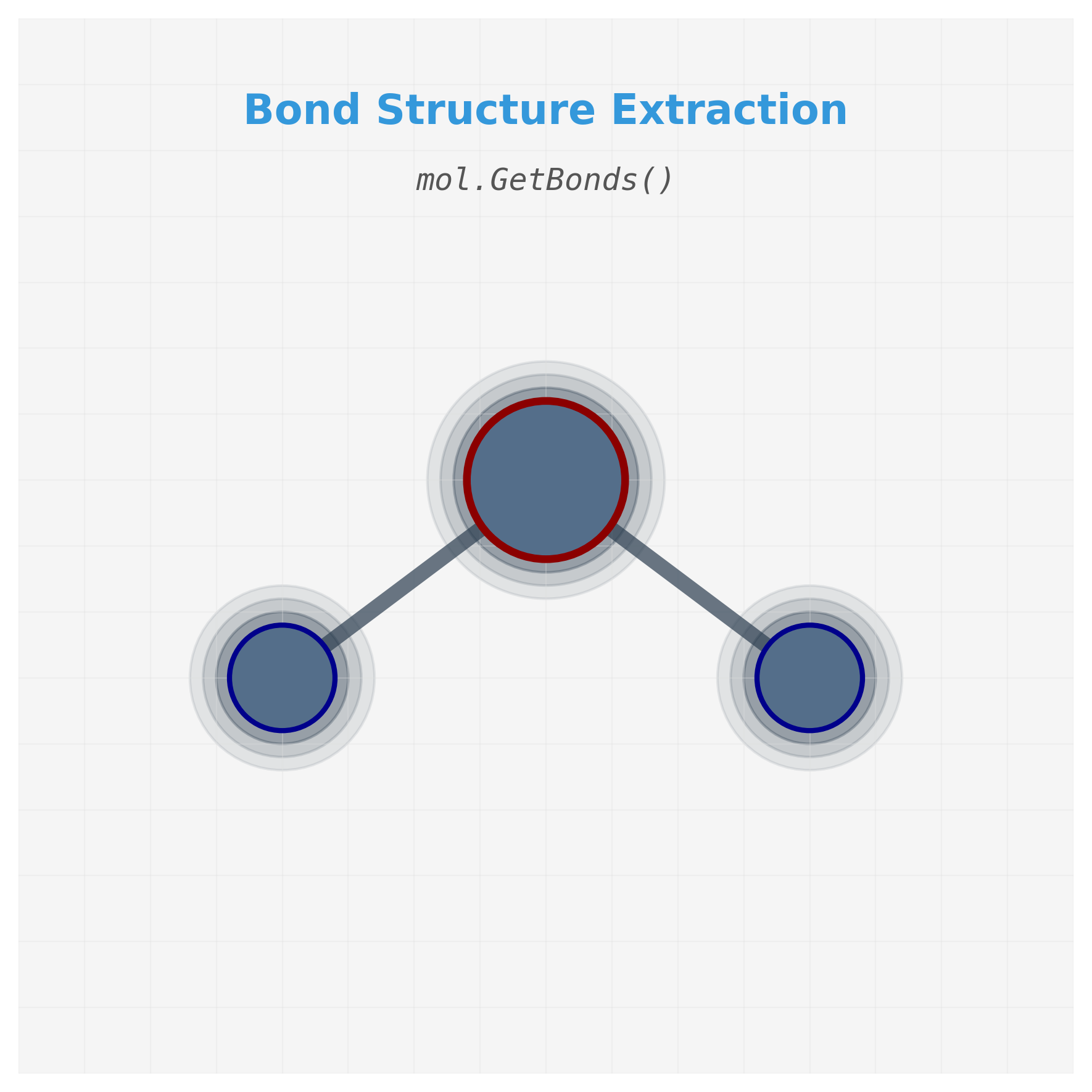

2. Access the bond structure (graph edges)

Once we have the molecule, we want to know which atoms are connected—this is the basis for constructing a graph. RDKit stores this as a list of Bond objects, which we can retrieve using mol.GetBonds().

Let’s break down the functions used here:

-

mol.GetBonds(): Returns a list of bond objects in the molecule. Each bond connects two atoms. -

bond.GetBeginAtomIdx()andbond.GetEndAtomIdx(): These return the indices (integers) of the two atoms that are connected by the bond. -

mol.GetAtomWithIdx(idx).GetSymbol(): This retrieves the chemical symbol (e.g. “H”, “O”) of the atom at a given index.

Extracting bond connectivity from RDKit molecule object. Each bond connects two atoms identified by their indices, forming the edges of our molecular graph.

Extracting bond connectivity from RDKit molecule object. Each bond connects two atoms identified by their indices, forming the edges of our molecular graph.

▶ Click to see code: Extracting graph connectivity

# Print all bonds in the molecule in the form: Atom(index) -- Atom(index)

print("Water molecule connections:")

for bond in water.GetBonds():

atom1_idx = bond.GetBeginAtomIdx() # e.g., 0

atom2_idx = bond.GetEndAtomIdx() # e.g., 1

atom1 = water.GetAtomWithIdx(atom1_idx).GetSymbol() # e.g., "O"

atom2 = water.GetAtomWithIdx(atom2_idx).GetSymbol() # e.g., "H"

print(f" {atom1}({atom1_idx}) -- {atom2}({atom2_idx})")

# Output:

# Water molecule connections:

# O(0) -- H(1)

# O(0) -- H(2)

- Bond Retrieval: The

mol.GetBonds()function returns a list of bond objects in the molecule. Each bond object represents a connection between two atoms. - Atom Indices: For each bond,

bond.GetBeginAtomIdx()andbond.GetEndAtomIdx()return the indices of the two atoms connected by the bond. These indices correspond to the positions of the atoms in the molecule object. - Atom Symbols: The

mol.GetAtomWithIdx(idx).GetSymbol()function retrieves the chemical symbol (e.g., “H” for hydrogen, “O” for oxygen) of the atom at a given index. This helps in identifying the types of atoms involved in each bond. - Connectivity Representation: The output shows the connectivity of the water molecule as:

O(0) -- H(1)O(0) -- H(2)

This indicates that the oxygen atom (index 0) is bonded to two hydrogen atoms (indices 1 and 2). This connectivity information is crucial for constructing the graph representation of the molecule, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

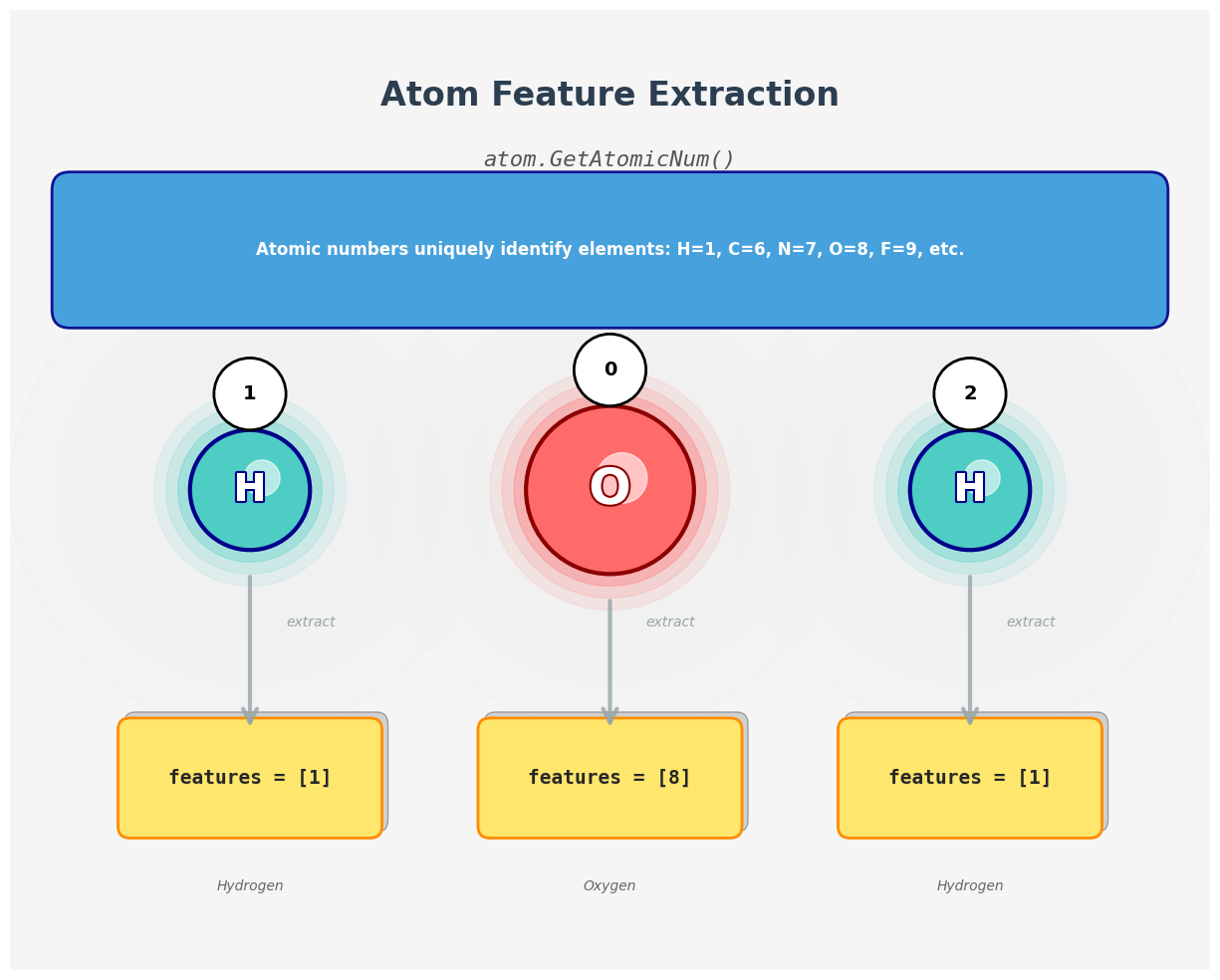

3. Extract simple atom-level features

Each atom will become a node in our graph, and we often associate it with a feature vector. To keep things simple, we start with just the atomic number.

Here’s what each function does:

-

atom.GetAtomicNum(): Returns the atomic number (integer) for the element, e.g., 1 for hydrogen, 8 for oxygen. -

mol.GetAtoms(): Returns a generator over allAtomobjects in the molecule. -

atom.GetSymbol(): Returns the chemical symbol (“H”, “O”, etc.), useful for printing/debugging.

Atom-to-feature mapping. The atomic number provides a simple yet effective initial representation for each node in the molecular graph.

Atom-to-feature mapping. The atomic number provides a simple yet effective initial representation for each node in the molecular graph.

▶ Click to see code: Atom feature extraction

# For each atom, we print its atomic number

def get_atom_features(atom):

# Atomic number is a simple feature used in many models

return [atom.GetAtomicNum()]

# Apply to all atoms in the molecule

for i, atom in enumerate(water.GetAtoms()):

features = get_atom_features(atom)

symbol = atom.GetSymbol()

print(f"Atom {i} ({symbol}): features = {features}")

# Output

# Atom 0 (O): features = [8]

# Atom 1 (H): features = [1]

# Atom 2 (H): features = [1]

- Feature Extraction Function:

- The

get_atom_features(atom)function extracts the atomic number of each atom usingatom.GetAtomicNum(). This is a simple yet powerful feature for distinguishing between different elements. - The atomic number is a unique identifier for each element: 1 for hydrogen (H) and 8 for oxygen (O).

- The

- Iterating Over Atoms:

- The

mol.GetAtoms()function returns a generator that iterates over allAtomobjects in the molecule. - For each atom, we retrieve its atomic number and store it as a feature vector (a list containing a single element).

- The

- Output Explanation:

- The output lists each atom in the molecule along with its atomic number:

Atom 0 (O): features = [8]: The oxygen atom (index 0) has an atomic number of 8.Atom 1 (H): features = [1]: The first hydrogen atom (index 1) has an atomic number of 1.Atom 2 (H): features = [1]: The second hydrogen atom (index 2) also has an atomic number of 1.

- The output lists each atom in the molecule along with its atomic number:

- Significance:

- These atomic numbers serve as the initial node features for the molecular graph. In more advanced models, additional features (e.g., degree, hybridization, electronegativity) can be included to capture more complex chemical properties.

- By representing each atom with its atomic number, we provide a basic yet meaningful input for graph neural networks to learn from the structural and chemical properties of the molecule.

In summary, this code demonstrates how to extract simple yet essential features from each atom in a molecule, laying the foundation for constructing informative node attributes in molecular graphs.

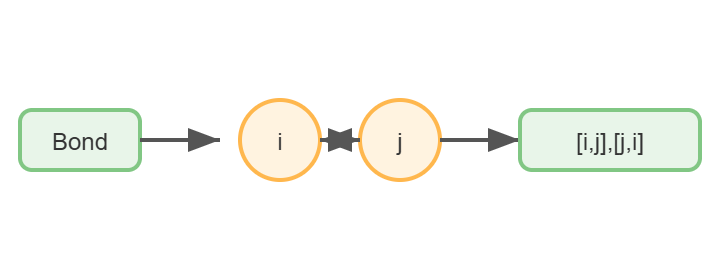

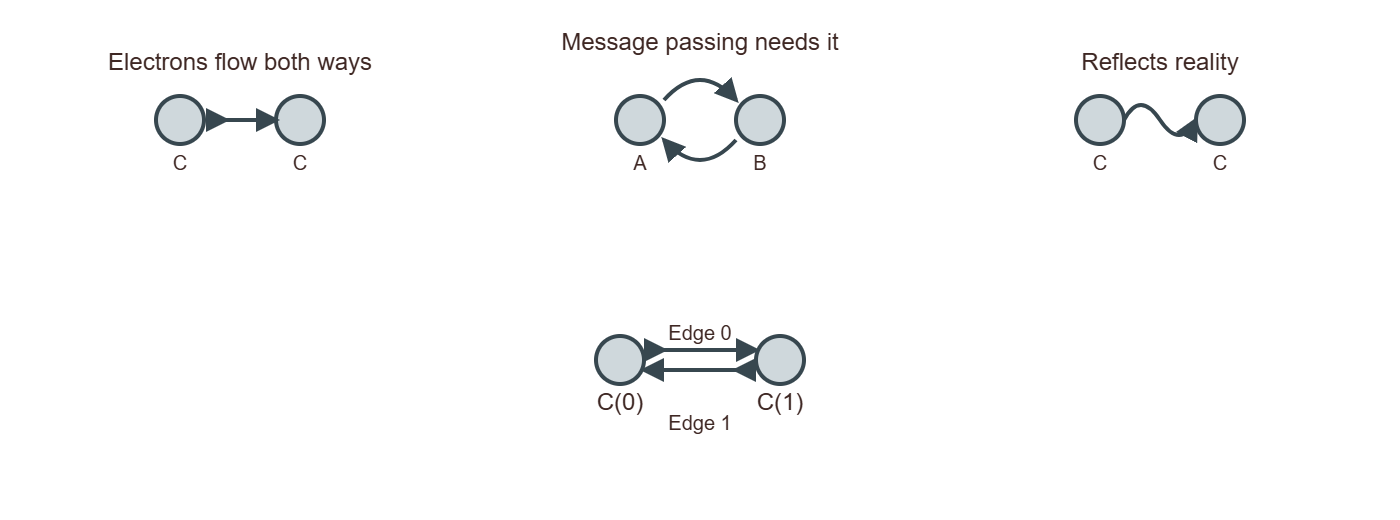

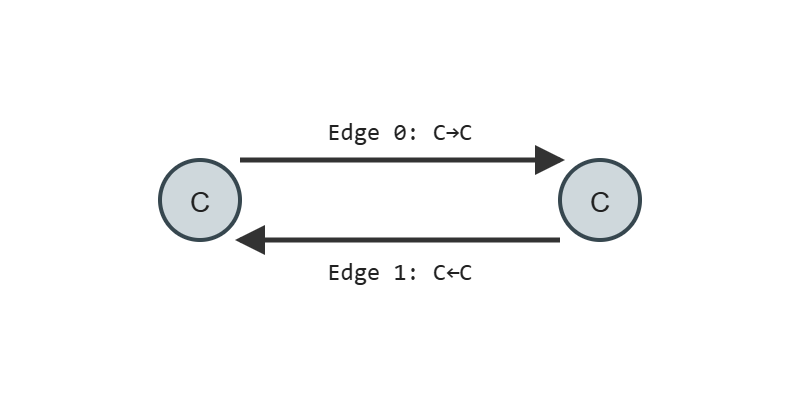

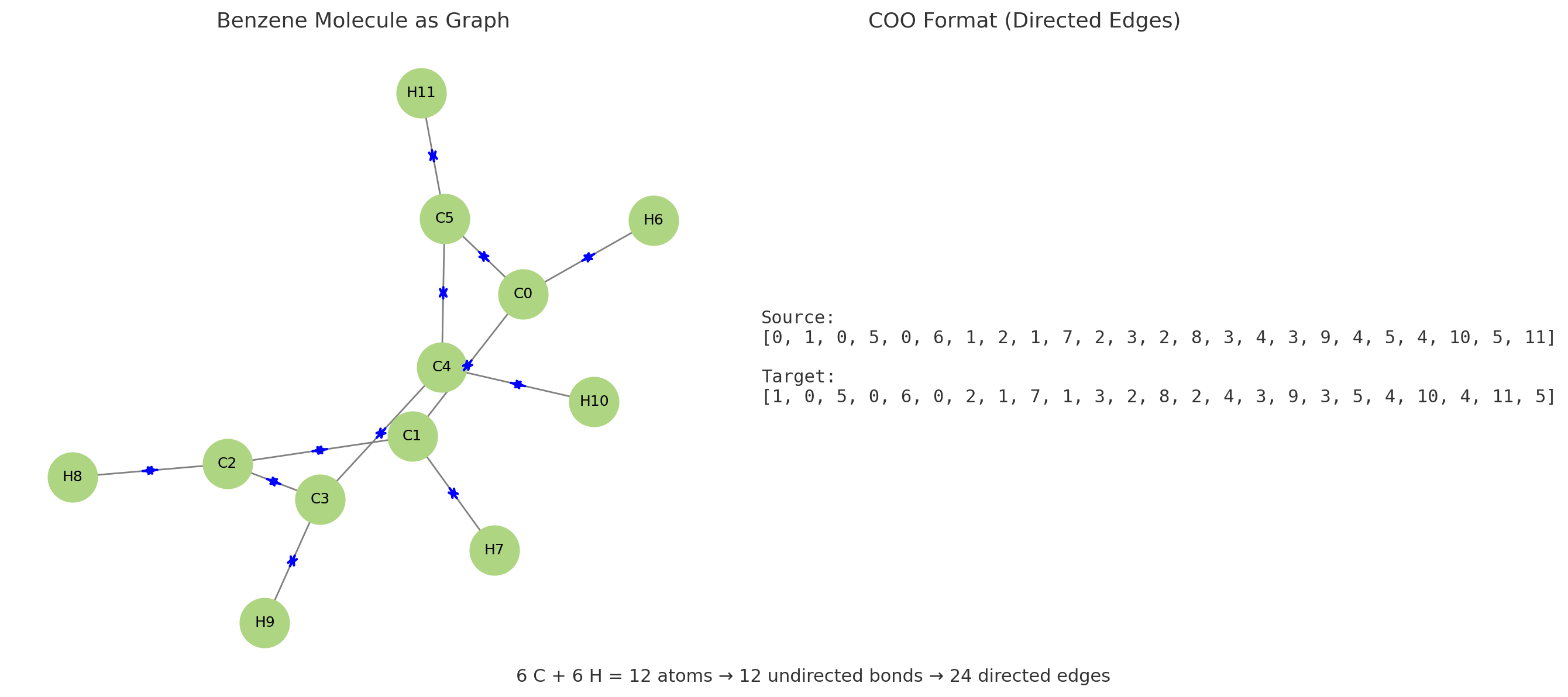

4. Build the undirected edge list

Now we extract the list of bonds as pairs of indices. Since GNNs typically use undirected graphs, we store each bond in both directions (i → j and j → i).

Functions involved:

bond.GetBeginAtomIdx(),bond.GetEndAtomIdx()(as above)- We simply collect

[i, j]and[j, i]into a list of edges.

Building an undirected edge list from molecular bonds. Each bond generates two directed edges (i→j and j→i) to ensure bidirectional message passing in the GNN.The complete edge list for water molecule. Bidirectional edges enable information flow in both directions during GNN message passing.

Building an undirected edge list from molecular bonds. Each bond generates two directed edges (i→j and j→i) to ensure bidirectional message passing in the GNN.The complete edge list for water molecule. Bidirectional edges enable information flow in both directions during GNN message passing.

▶ Click to see code: Edge extraction

def get_edge_list(mol):

edges = []

for bond in mol.GetBonds():

i = bond.GetBeginAtomIdx()

j = bond.GetEndAtomIdx()

edges.append([i, j])

edges.append([j, i]) # undirected graph: both directions

return edges

# Run on water molecule

water_edges = get_edge_list(water)

print("Water edges:", water_edges)

# Output

# Water edges: [[0, 1], [1, 0], [0, 2], [2, 0]]

- Function Definition:

get_edge_list(mol): This function takes an RDKit molecule object (mol) as input and returns a list of edges representing the connectivity between atoms.

- Edge Extraction:

mol.GetBonds(): This method retrieves a list of bond objects from the molecule. Each bond object represents a connection between two atoms.- For each bond,

bond.GetBeginAtomIdx()andbond.GetEndAtomIdx()are used to get the indices of the two atoms connected by the bond. These indices are integers that uniquely identify atoms within the molecule. - The edge list is constructed by appending both

[i, j]and[j, i]to theedgeslist. This ensures that the graph is undirected, which is essential for GNNs. In an undirected graph, the relationship between nodes is bidirectional, meaning that if atomiis connected to atomj, then atomjis also connected to atomi.

- Output:

- The function returns the complete edge list, which includes all pairs of connected atoms in both directions.

- For the water molecule (H₂O), the output is:

Water edges: [[0, 1], [1, 0], [0, 2], [2, 0]][0, 1]and[1, 0]: These pairs represent the bond between the oxygen atom (index 0) and the first hydrogen atom (index 1).[0, 2]and[2, 0]: These pairs represent the bond between the oxygen atom (index 0) and the second hydrogen atom (index 2).

Each pair represents one connection (bond) between atoms. Including both directions ensures that during message passing, information can flow freely from each node to all its neighbors.

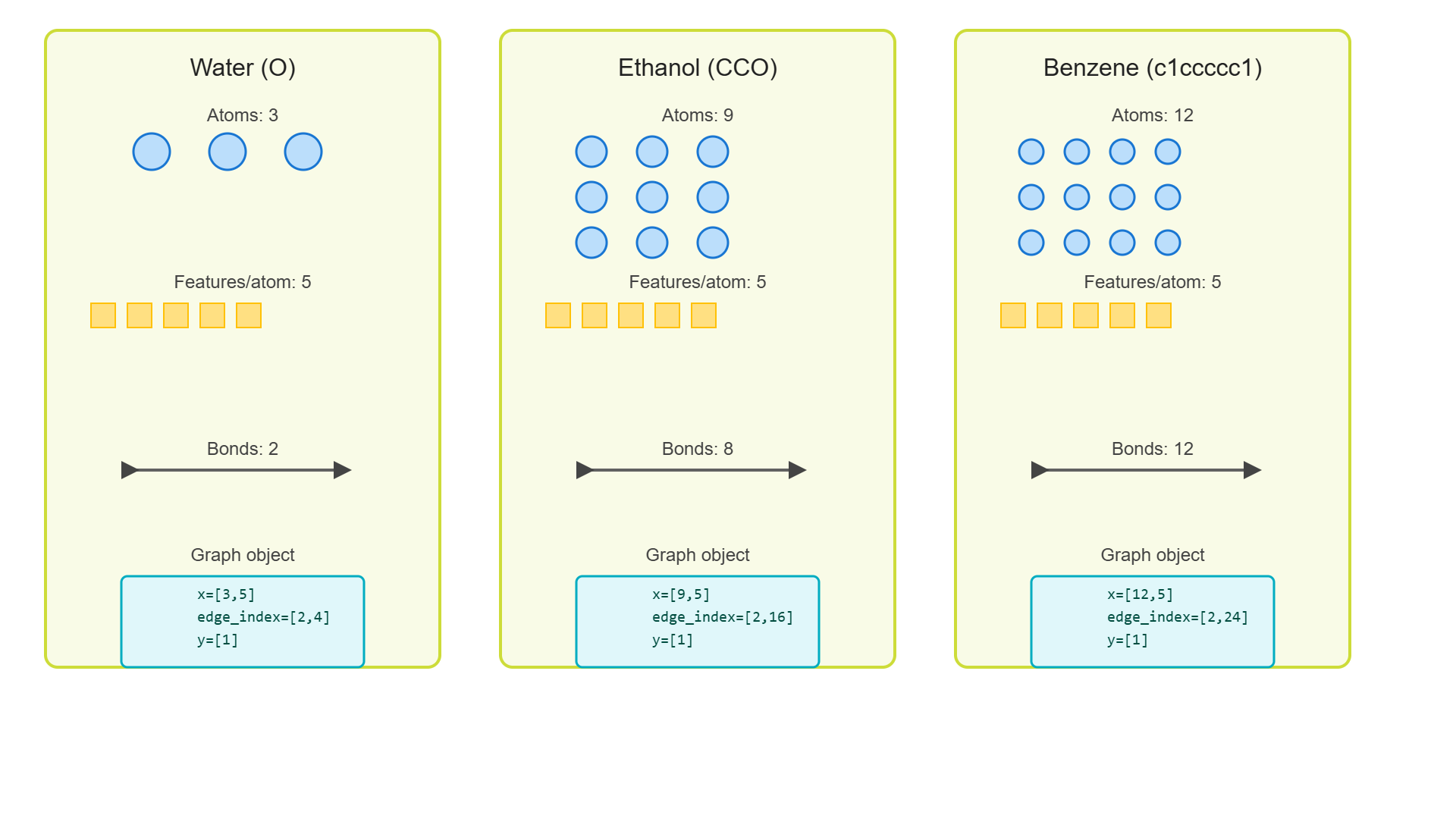

Using RDKit, we can get the chemical structures and corresponding graph statistics for common molecules (water, ethanol, benzene, and aspirin). Each molecule is shown with its 2D structure alongside graph metrics including node count, edge count, and atom type distribution.

Using RDKit, we can get the chemical structures and corresponding graph statistics for common molecules (water, ethanol, benzene, and aspirin). Each molecule is shown with its 2D structure alongside graph metrics including node count, edge count, and atom type distribution.

Summary: The Power of Molecular Graphs

Let’s recap what we’ve learned:

- Molecules are naturally graphs - atoms are nodes, bonds are edges

- Traditional methods lose structural information - they treat molecules as bags of features

- GNNs preserve molecular structure - they process the actual connectivity

- Message passing allows context learning - atoms learn from their chemical environment

- Property prediction becomes structure learning - the model learns which structural patterns lead to which properties

In the next section, we’ll dive deep into how message passing actually works, building our understanding step by step until we can implement a full molecular property predictor.

3.3.2 Message Passing and Graph Convolutions

Completed and Compiled Code: Click Here

At the core of a Graph Neural Network (GNN) is the idea of message passing. The goal is to simulate an important phenomenon in chemistry: how electronic effects propagate through molecular structures via chemical bonds. This is something that happens in real molecules, and GNNs try to mimic it through mathematical and computational means.

Let’s first look at a chemistry example. When a fluorine atom is added to a molecule, its high electronegativity doesn’t just affect the atom it is directly bonded to. It causes that carbon atom to become slightly positive, which in turn affects its other bonds, and so on. The effect ripples outward through the structure.

This is exactly the kind of structural propagation that message passing in GNNs is designed to model.

Comparison of electronic effects propagation in real molecules (left) versus GNN simulation (right). The fluorine atom’s electronegativity creates a ripple effect through the carbon chain, which GNNs capture through iterative message passing.

Comparison of electronic effects propagation in real molecules (left) versus GNN simulation (right). The fluorine atom’s electronegativity creates a ripple effect through the carbon chain, which GNNs capture through iterative message passing.

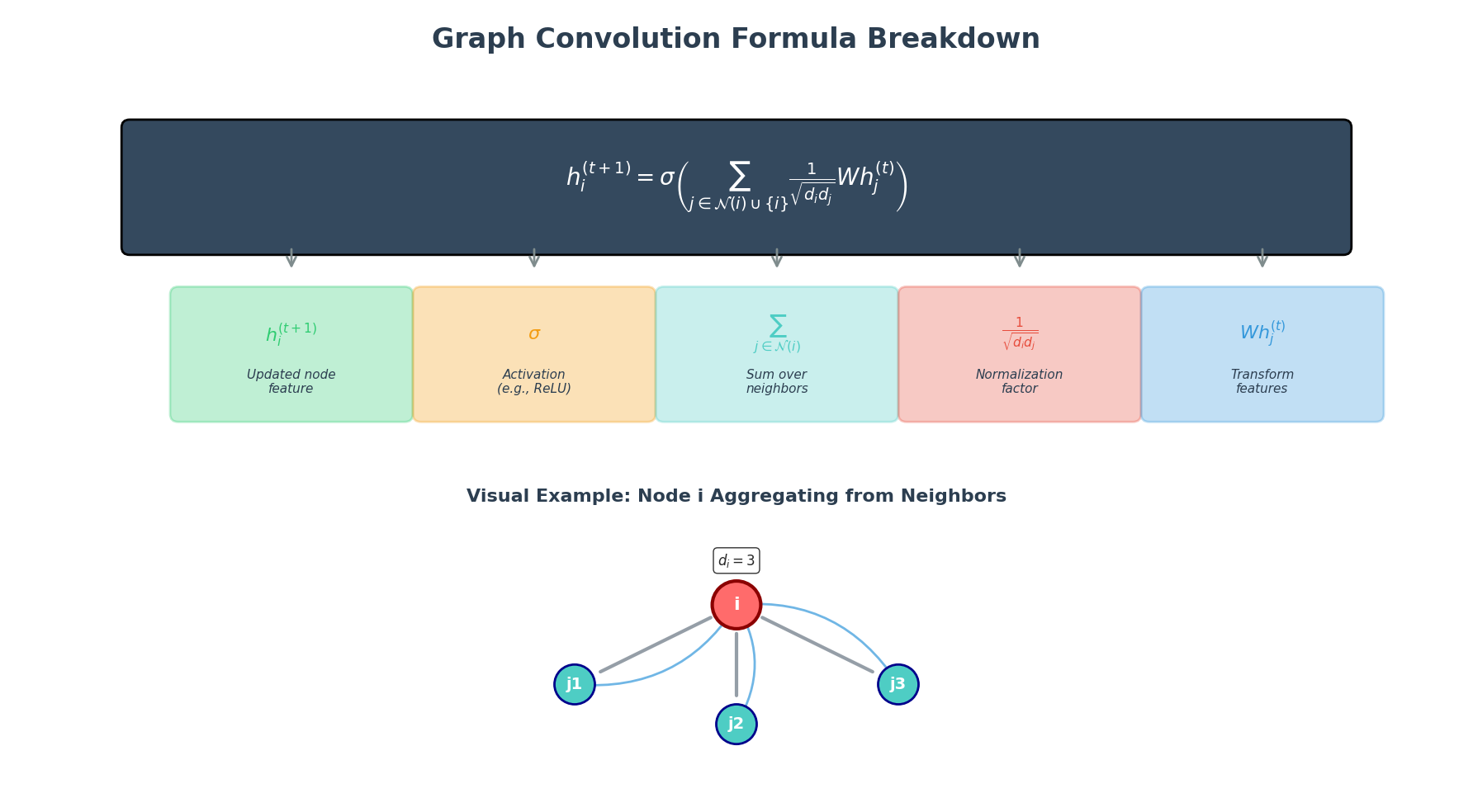

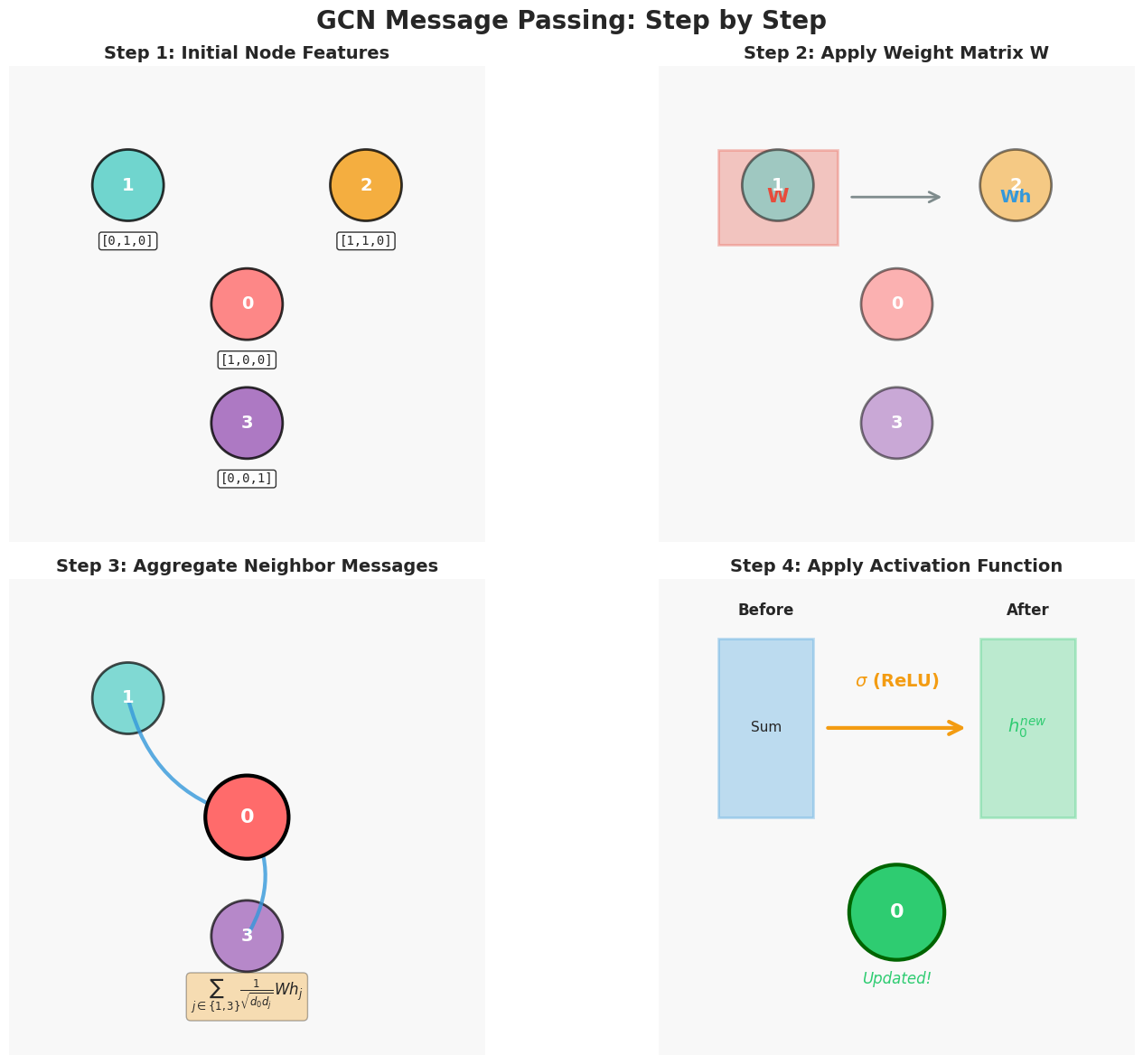

The structure of message passing: what happens at each GNN layer?

Even though the idea sounds intuitive, we need a well-defined set of mathematical steps for the computer to execute. In a GNN, each layer usually follows three standard steps.

The three standard steps of message passing in GNNs: (1) Message Construction - neighbors create messages based on their features and edge properties, (2) Message Aggregation - all incoming messages are combined using sum, mean, or attention, (3) State Update - nodes combine their current state with aggregated messages to produce new representations.

The three standard steps of message passing in GNNs: (1) Message Construction - neighbors create messages based on their features and edge properties, (2) Message Aggregation - all incoming messages are combined using sum, mean, or attention, (3) State Update - nodes combine their current state with aggregated messages to produce new representations.

Step 1: Message Construction

For every node $i$, we consider all its neighbors $j$ and create a message $m_{ij}$ to describe what information node $j$ wants to send to node $i$.

This message often includes:

- Information about node $j$ itself

- Information about the bond between $i$ and $j$ (e.g., single, double, aromatic)

Importantly, we don’t just pass raw features. Instead, we use learnable functions (like neural networks) to transform the input into something more meaningful for the task.

Step 2: Message Aggregation

Once node $i$ receives messages from all neighbors, it aggregates them into a single combined message $m_i$.

The simplest aggregation method is to sum all incoming messages:

\[m_i = \sum_{j \in N(i)} m_{ij}\]Here, $N(i)$ is the set of all neighbors of node $i$. This step is like saying: “I listen to all my neighbors and combine what they told me.”

However, in real chemistry, not all neighbors are equally important:

- A double bond may influence differently than a single bond

- An oxygen atom might carry more weight than a hydrogen atom

That’s why advanced GNNs often use weighted aggregation or attention mechanisms to adjust how each neighbor contributes.

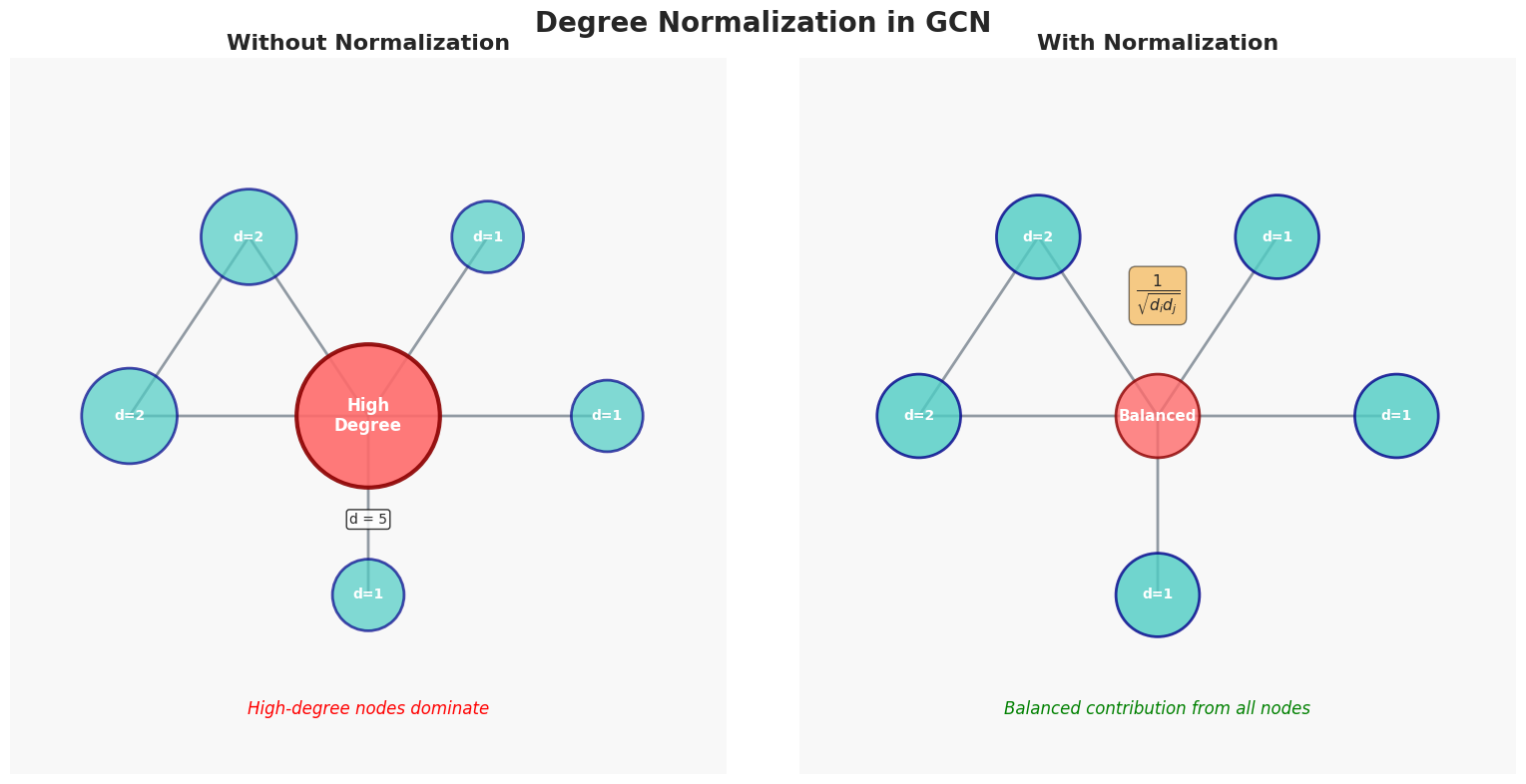

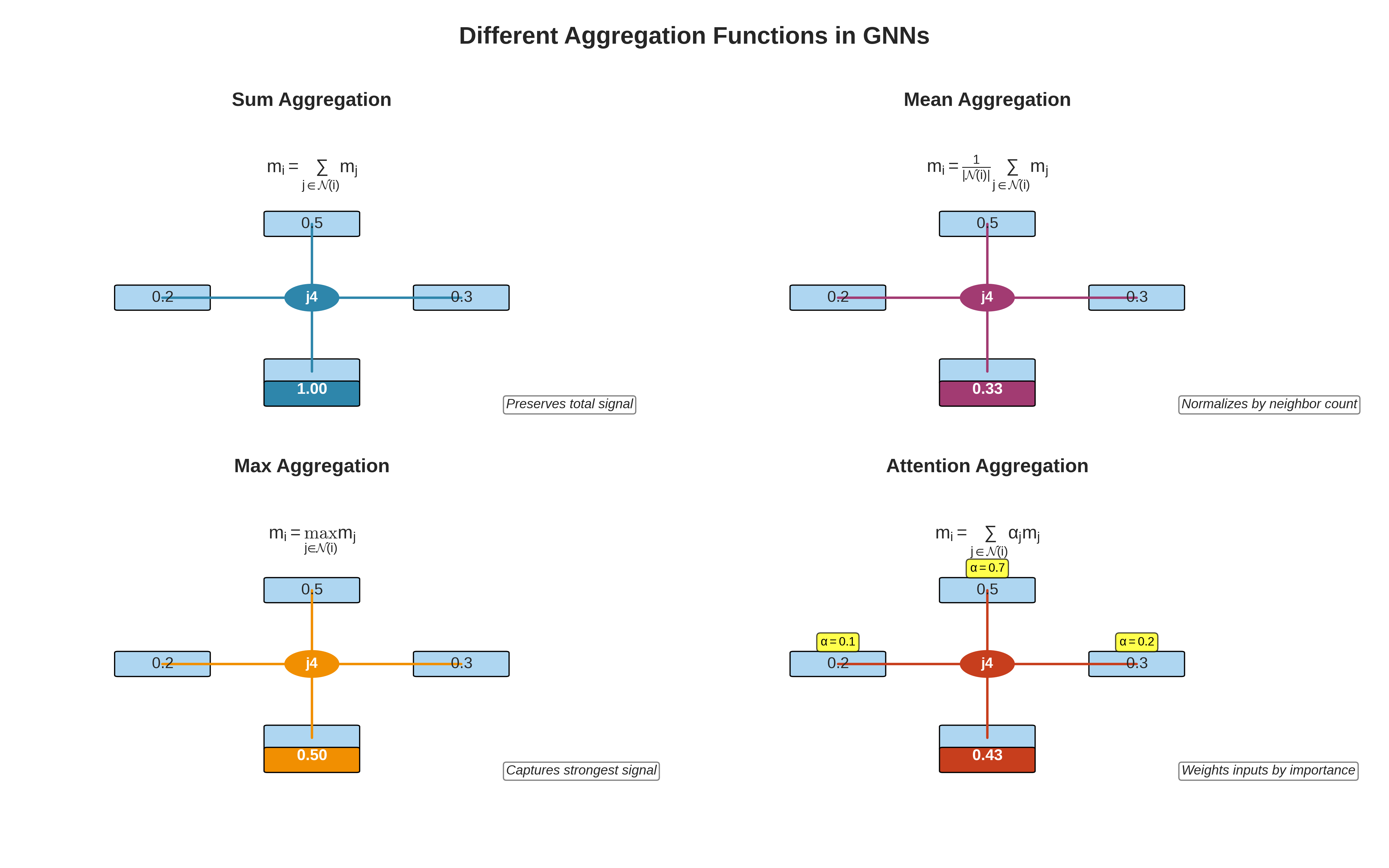

Different aggregation functions in GNNs. Sum preserves total signal strength, Mean normalizes by node degree, Max captures the strongest signal, and Attention weights messages by learned importance scores.

Different aggregation functions in GNNs. Sum preserves total signal strength, Mean normalizes by node degree, Max captures the strongest signal, and Attention weights messages by learned importance scores.

Step 3: State Update

Finally, node $i$ uses two inputs:

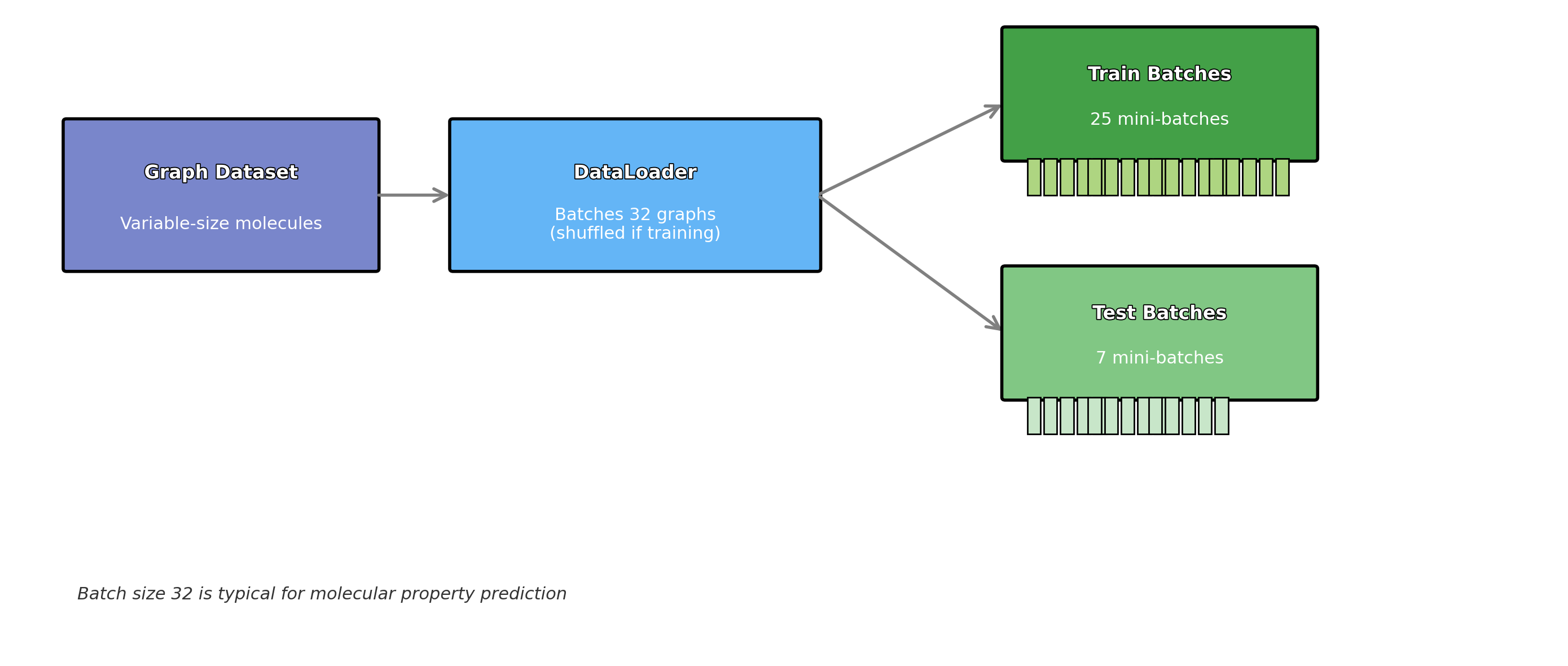

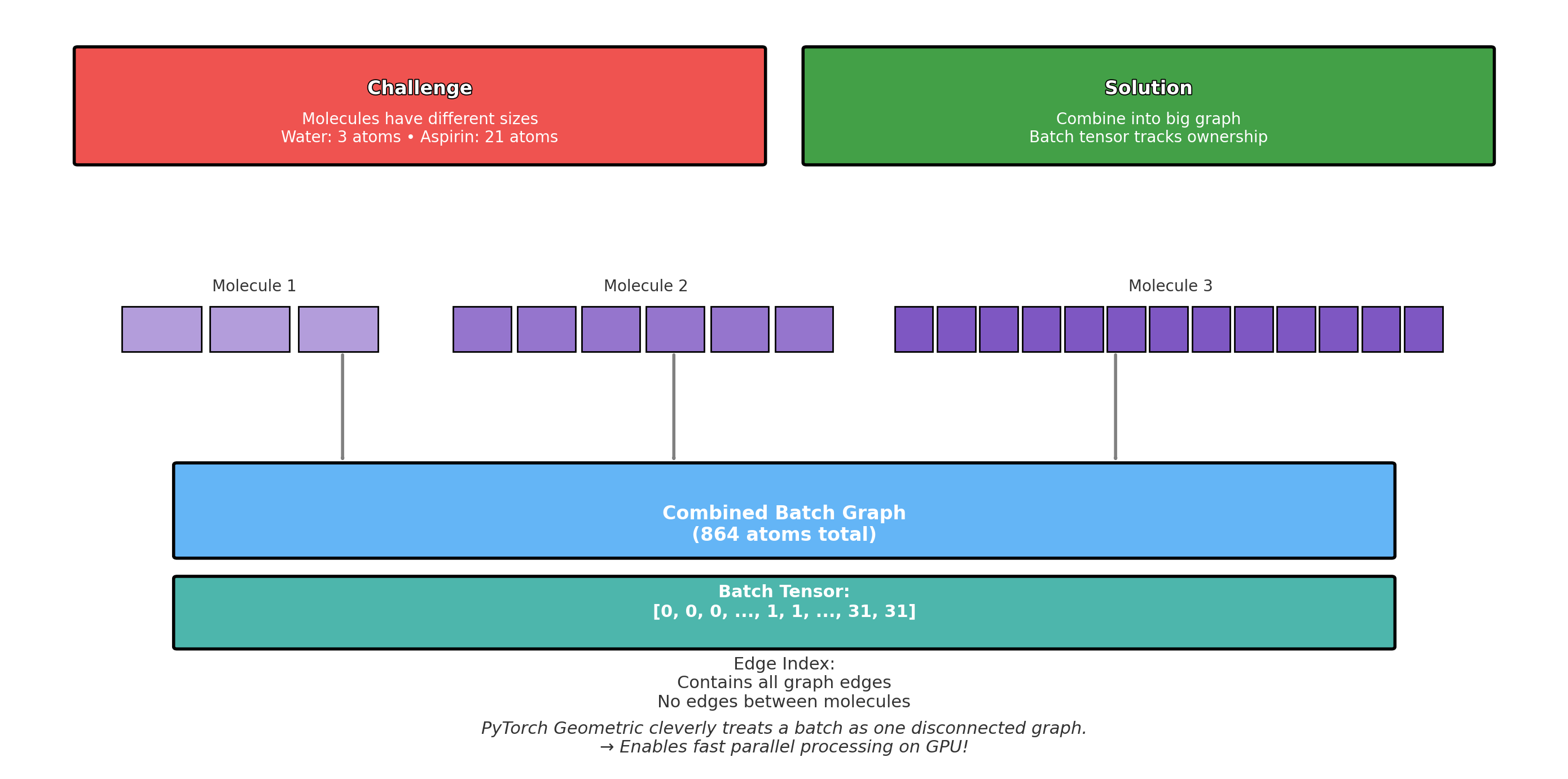

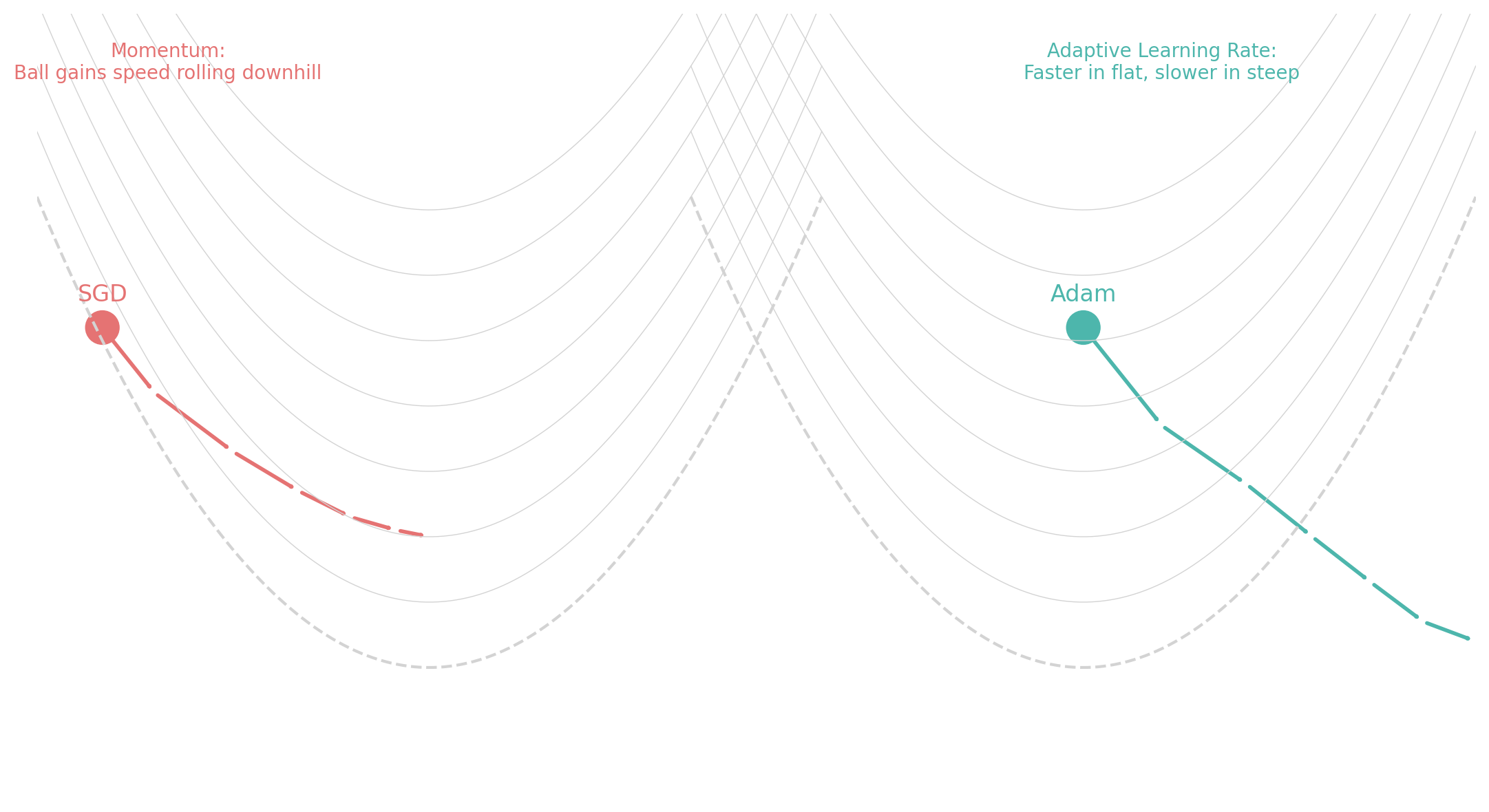

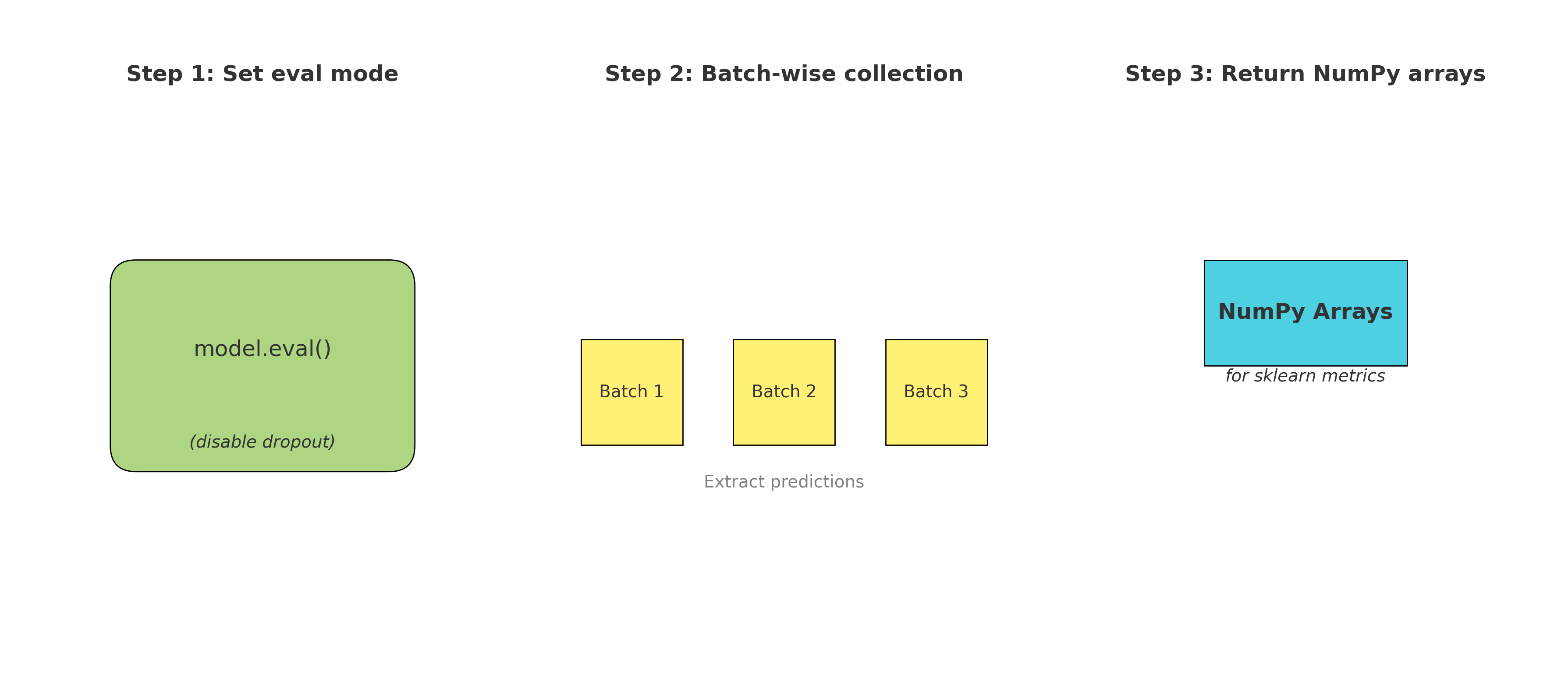

- Its current feature vector $h_i^{(t)}$